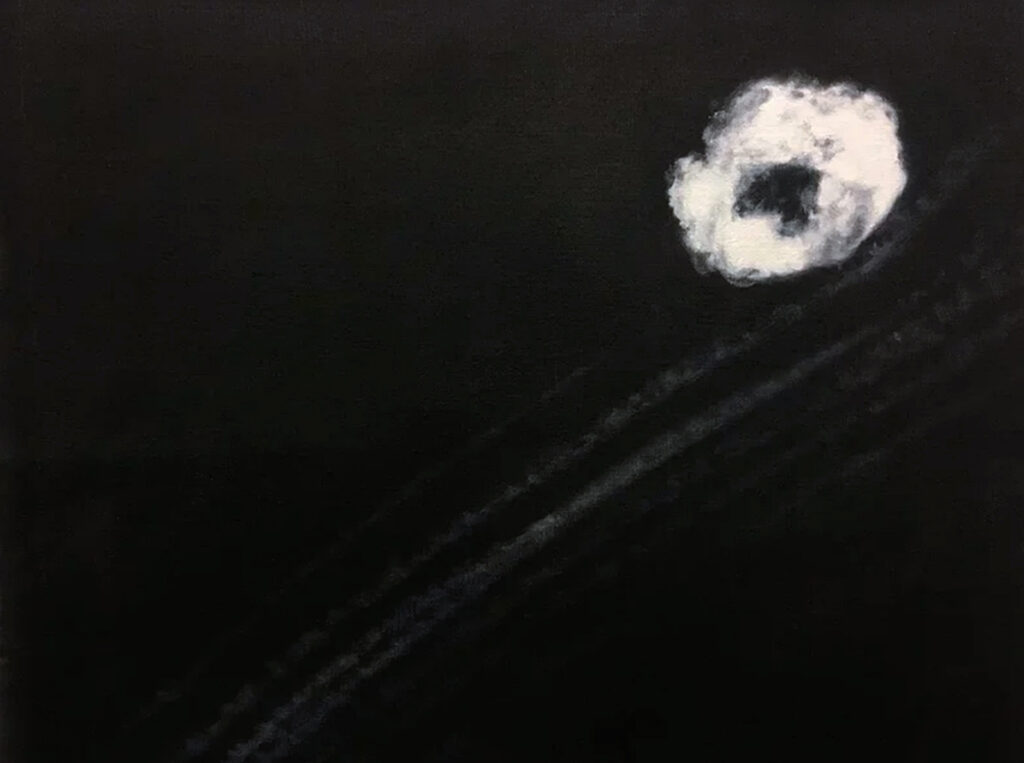

Kirsty Harris depicts the most iconic man-made event that might take place in a landscape: the detonation of the atom bomb.

Often working at scale, Harris confronts her audience with a vision of awe and beauty. Mushroom clouds hang over desolate expanses of the Nevada desert, provoking contemplation at the intersection of humanity, brutality, technology and nature.

Harris’s practice is steadfast; her paintings are informed by deep research, and this arduous process is echoed in depictions of a split-second event painted over a period of several months.

– Zavier Ellis for the Saatchi exhibition 2023

CBP: Your paintings reconstruct photographic documents of the atomic bomb tests, often in the Nevada desert, in a range of exhibition display formats. Can you introduce the core themes of your work?

KH: I am interested in the way these events from history disrupt and scar those barren landscapes. These swirling, bubbling apparitions are like curses or spells that we’ve cast on ourselves, so violent.

My work might feel confrontational, maybe abrupt at first, then hopefully unravelling into something more. I am also drawn in by the stories and myths that run alongside the scientific nature of the subject. We all know that beauty doesn’t have a moral duty to be inherently good. It’s something I think about, the push and pull of awe. The tests made in the desert are so fascinating, the photographs are very rich, colourful, and vivid, due to the way the light refracts and the type of film used. These practice runs at annihilation are so beautiful – it’s unreal. It’s dark.

CBP: You talk about early memories and family history in attending CND rallies as a child. Can you discuss this influence on the subject of your painting today?

KH: As I was becoming more and more interested in landscape painting I noticed they all have something occurring, could be farmers, the sun setting, a stormy sky, a battle, a tiny stream. Alone at Tate Modern I was looking at a painting of a single cloud by Richter and then suddenly something clicked in my head. I was walking around, eyes wide with a slack jaw, thinking “oh wow this is what I must do. Paint mushroom clouds.”

The anticipation of piling onto a coach and ending up somewhere waving my homemade banner and singing and chanting at CND protests are evocative memories from my childhood. In our doorway at home, visitors were welcomed by a massive poster of Thatcher & Reagan parodied in a Gone With The Wind movie-style poster, complete with a billowing mushroom cloud in the background. We collected protest badges and leaflets and the atmosphere was potent and thrilling, but I didn’t catch on to what we were shouting about until later. So it was always there in me. A weird relationship with the subject matter.

CBP: Many years ago I visited a small museum in the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, Albuquerque, New Mexico near the atomic bomb test sites. The original photographs of the test bombs were shown alongside reportage photographs of the real bombs and their impact (I think). Also displayed was a fascinating comic book type narrative depicting the daily life of the factory workers who built the bomb and their families. I recall being quietly absorbed by the experience, though I questioned what it was I was looking at, in terms of archive material, as a museum display, and how it made me feel.

When you research and paint your subject, how do you negotiate what you feel about the source material and its transition into you what you are painting? Has it changed over time?

KH: It feels like science fiction.

Through the extensive documentation of nuclear detonations, I can view how these expansive entities change millisecond to millisecond, from the fireball to the pure white cloud left hanging at the end. In my publication, Completely er, unfolding itself (2019), I transcribed the first live official television broadcast of an atomic explosion – given the code name ‘Charlie’ – in 1942. The reporters struggle, grasping for the language to describe the mushroom cloud in front of them – and I get where they were coming from.

We are in such close proximity right now to digital versions of war. Scrolling through instagram you have temu trying to sell you some shitty plastic drawers and then 1 second later a mother holding her tiny dead child wrapped in tarpaulin, and worse. It’s so brutal.

I keep thinking how can we be doing that to ourselves, can they never see themselves in the faces of the people they kill and torture. Nothing is worth this brutality.

I guess my brain is always negotiating how much to watch in order to feel informed but not go reeling into despair, like all of us.

CBP: In 2007 Mark Wallinger created ‘State Britain’, for the Tate, a meticulous recreation of real-life antiwar demonstrator Brian Haw’s banned protest camp outside the Houses of Parliament. Rather than importing elements of the real camp as a readymade, Wallinger chose to painstakingly recreate it as a painted facsimile. This solitary studio activity would have given him time to reflect on its impact, the life sacrifice Brian Haw made, and what he as an artist was recreating.

How does time and the meticulous process of painting your subject impact on the meaning of the work for you?

KH: Like the women at Greenham Common, Brian Haw was the artwork, the awesome spectacle. Inconvenient clutter. The resilience is truly remarkable. Wallinger’s piece pays tribute to this but, a little like the fake Lascaux caves. Good if you can never see the real thing, but there’s no point looking up close. I found the political implications of it very interesting.

Large paintings take me such a long time, it’s ridiculous.

I have to continually change my vantage point. If it’s possible I turn the painting upside down, take photos of it and desaturate it. Stand up painting, sit down painting. Up the ladder, sat on the floor. I always imagine the next one will be more straightforward but in 25 years, that has never happened, so why would it now? But while there is much anxiety balled up in the action of painting, it is also a hypnotic and calming process. Studying a millisecond of time for so long. I don’t know if it matters to anyone else how long I’ve looked at the painting or the source material, but the act of looking is so important to me. Displaying a painting on your wall at home, you might not realise it but with so much flashing and moving imagery invading our lives (with invitation) a semi-permanent, static, image has a big impact. I love it when there are different layers of meaning to dive into, even if they are not explicit your subconscious will identify them. Looking at an artwork every day builds up a special relationship and enriches the way my mind moves.

CBP: Scale feels important both in terms of the impact of your subject for the viewer and your immersion into it when painting it. Can you talk about this aspect of the work?

KH: When you start a painting, there are near unlimited decisions to make. One I used to have trouble with was how big it should be. So I started to use data to construct systems that help me decide. In my paintings, often each square inch (or centimetre) of linen represents a certain number of tons of TNT. This in turn is the unit of measurement chosen, by the military, to denote the yield of the detonation.

These hidden codes might reward an inquisitive viewer.

Really, what I want to do is make paintings so vast that that’s all they see and think about for a moment.

Investigating ideas of scale in a different way: Since 2013 I have been adding to and updating an audio composition entitled How I Learned to Stop Worrying (1945-2024). It is a musical account of every officially recorded nuclear explosion detonated between 1945 and the present day: each different instrument represents a country that partook; each month in history lasts a second on the recording; each note played depicts a single bomb. Eight musicians contributed to the piece and it was quite an epic translation of data to plot out the notes.

CBP: Can you reveal some of the mark making techniques and tools you use in your painting.

KH: On my larger paintings I staple the linen flat to the wall and then prime it with clear primer. This enables me to really push on the canvas without worrying if I will hit the crossbar. I would love to be laying down decisive, thick, final brush marks, but what comes out is me dabbing layers and layers of thin oil paint, leaving it to evaporate and then repeating the process. My paintings are usually very matt which somehow feels right given that I’m painting dust clouds and sand half the time.

I painted a lot of small paintings on glass during lockdown.

There was something comforting about the contained nature of those pieces. It is quite a different process but still I am basically dabbing on paint until it gets thick enough to create some depth. In a development from these smaller pieces I created a much larger light box piece, Blue Danube, 2023. It plays with the notions of nuclear tourism, emitting its own light in a kind of perverse advert.

CBP: Your titles are short but ranging from factual to enigmatic, how do title your work?

KH: Hard to explain how some titles come to me. A lot of the detonations use people’s names for code names, a bit like cyclones.

Some of my favourites:

“The instrument is not the Music” is the title of a tapestry where the image is a female scientist inspecting and testing a metal instrument. A still from a British documentary it shows the intricate process in a factory where workers unknowingly fabricate the components that will eventually be assembled to create an atomic bomb. tbf my boyfriend came up with that one. He is great at titles if I get stuck.

“Blue Danube” I liked because it is a river (starting in the Black Forest and ending in the Black Sea) a piece of classical music and a bomb. All the Bs, the Beautiful Blue Danube.

Always noting potential titles down in my phone notes, I also dedicate time to skim reading when I need quite a few titles at once. They always come!

CBP: Can you talk about your studio practice routine when carrying out archival research?

KH: There is the National Archives (UK) and Internet archives (USA) which I find very useful. I trawl through images via the normal channels and in addition watch out for vintage postcards on ebay, old photographs that people have sent me from their Uncle or Grandad’s collection. Declassified documents made into pdfs. We have a decent projector at home now so it’s great to watch documentaries on a large screen. Sometimes I take screenshots from military footage so the freeze-frame I choose may not have been studied widely. It’s interesting how in some images, due to the way the camera has responded, the sky looks black and the clouds are bright white. I have some exciting opportunities coming up, some top secret documents that someone is going to let me look through. And I’d like to work out ways to access small archives. There is one in particular in Germany that looks amazing.

At the moment I’m looking for glow.

CBP: What projects are you working on at the moment?

KH: I have time to settle into the studio right now and test out some things I have been thinking through. Last year was a busy one with a solo show at Studio KIND and a big group show at Saatchi Gallery. I am looking forward to a group show in London with some top painters (heroes) next year. Plus a possible group show in New York, just waiting to find out. I also have a soft focus vision of a show in the UK in a massive derelict space. It will be nice to hibernate like a little bear in my studio this winter and come back with new energies.

Kirsty Harris b. 1978 Raised in Yorkshire, artist and curator based in east London.

Co-founder of Come Quick Disaster and on the steering committee for Mental Health Arts organisation – Broken Grey Wires.

Recent solo and 2 person shows include; 2023 THAT LETHAL CLOUD, StudioKIND, Braunton, Devon, UK., HEAVY WEATHER, Splice, Perseverance Works, London, UK. 2022 INTERVENTION, DIY performances during the 59th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy.

Recent group exhibitions include; 2024 LATRINE’S HAUS OF ART, Vane Gallery, Gateshead, UK. SEX SELLS – BEYOND THE HISTORICAL MATRIX, Semjon Contemporary, Berlin, Germany, HOW LONG IS FOREVER, Galerie 37, Schöneberg, Berlin, Germany. BEYOND THE GAZE – RECLAIMING THE LANDSCAPE, Saatchi Gallery, London, UK. Curated by Zavier Ellis. 2023 A GENEROUS SPACE 3, Huddersfield Art Gallery, Yorkshire, UK. Invited by Karl Bielik, TWO PLUS TWO MAKES FOUR, Auxiliary Warehouse, Middlesbrough, UK. Curated by Broken Grey Wires, THE SUBVERSIVE LANDSCAPE, Tremenheere Gallery, Cornwall, UK. Curated by Hugh Mendes. X – Contemporary British Painting, Newcastle Contemporary Art, UK. Curated by Narbi Price. 2022 ROYAL ACADEMY SUMMER EXHIBITION, Royal Academy, London, UK.

Featured image- Charlie. by Kirsty Harris.