The Great Lakes Basin, once inundated by a vast ancient, shallow sea that covered much of central North America, is today revealing an abundance of fossil corals, invertebrates, and marine organisms found within many limestone formations uncovered by glaciers and erosion.

Haldimand and Norfolk County have especially become an attractive area to explore for fossils of marine organisms by both scientists and amateur fossil collectors who can travel to local locations such as Rock Point Provincial Park near Dunnville, Ontario.

However, these fossils represent more than just evidence of unique life forms that once numbered in the tens of thousands of species co-existing in a marine ecosystem. They are scientific evidence of marine ecosystems in ecological transition, shifting continents, changing climates, and a record of our planets’ every day rotation around the sun.

Many fossil corals found in Haldimand and Norfolk County date around 410 to 360 million years ago. It is a time geologically known as the “Devonian Period”, the “Devonian Reef” or the “Age of Fishes”. During this period, fishes of many different species became abundant in the fossil record. A partly submerged North America, or as yet to be formed Great Lakes Basin, was colliding with Europe close to the equator. Reef building environments began to develop and produce some of the largest reef complexes in the world.

The reef complexes were in large areas of shallow equatorial seas that existed between the continents.

Evidence of a saltwater sea supporting a vast coral reef system once covering southern Ontario over 400 million years ago in the form of fossilized coral deposits support the theory that a coral reef system existed for a very long time. It was in the basins of these former shallow seas that great quantities of rock salt, gypsum, and other types of minerals precipitated, and today, mining industries dig well below the lowest depths of Lake Erie to recover these minerals.

Exposure of reef basins varies and depends on how glaciers or water erosion has pushed or washed soil off bedrock. Under these conditions, a geologist’s field magnifying glass can help find very small fossils such as radiolarians and diatoms. Otherwise, larger fossils such as different varieties of bivalves (clams), trilobites, and even large fragments of fossilized coral are exposed. In some case, there are discoveries of fossilized marine organisms that are both rare and some times difficult to identify.

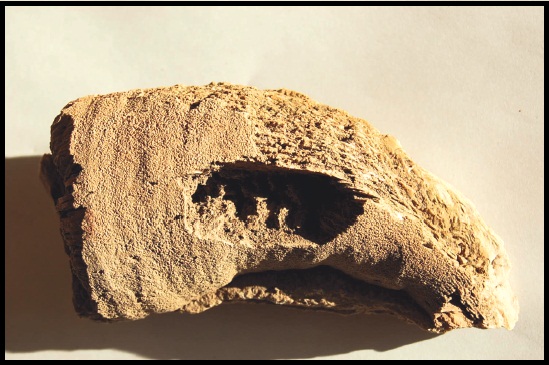

The fossilized remains of a Devonian Reef. Rock Point Provincial Park, Ontario.

Rock Point provincial park- exposed fossilized reef system holds an incredibly amount of fossils.

What ended these reef complexes and created one of the greatest mass extinction events of earth’s biota is not completely understood but was a combination of events that took place over a period of 25 million years.

Since species rely on a warm water marine ecosystem for their survival it would seem that a slow and gradual continental shift north from the equator would over time impact a large variety of marine species, including those supported by coral reefs. Therefore, events such as shifting continents, lowering of sea levels, climatic changes influencing land and sea ecologies, and/or possibly a glaciation had significant roles in the extinction of earth’s biodiversity.

The large deposits of fossil corals and invertebrates found in Norfolk and Haldimand County has been of great interest to scientists and fossil collectors for many decades. However, fossil collecting took on a new importance in the last 50-60 years when it was determined there was a connection between growth rings of coral skeletons with the number of days in a year.Scientists studying samples of coral skeletons from contemporary coral reef systems discovered growth rings on the outer surface of coral skeletons.

By studying a large sample of coral skeletons and determining how many growth rings represented a year’s growth of calcium carbonate, scientists were able to calculate an average of 360 rings per year. Thereby, approximately one growth ring represented one day’s growth for each day of the year. Taking this new information, scientists began collecting large numbers of exceptionally well-preserved coral fossils belonging to the Late Devonian Period. One particular species, found in the Great Lakes region, called a “Heliophylum halli” (see above) exhibited many growth rings developing in one year during this period. The result surprised even scientists.

Fossil coral showed there were approximately 400 growth rings per year 370 million years ago. Therefore, there were about 400 days in a year in the Devonian Period. Astronomers who have calculated that our earth’s rotation has been slowing at a rate of about 2 seconds every 100,000 years have since supported the new information.

Despite Haldimand and Norfolk County being a small example of a region once holding a thriving coral reef system, existing over 400 million years ago, the number of fossils of different species exposed is vast. Fossil corals, invertebrates, and species of marine organisms exist in many different shapes, sizes, and can be very fragile. Therefore, whether you are a scientist or amateur fossil collector, the next time you take a walk across the landscape to explore and search for fossils be sure to take along a fossil guide. You never know what new fossil discoveries you might make just walking across the countryside for an afternoon. For the Silo, Lorenz Bruechert.