Presenters at last year’s C.D. Howe Institute’s conference on Canada’s debt problem had some pointed advice for our federal and provincial governments:

- Canada’s public debt should be reduced about 10 percentage points of Canada’s GDP to ensure fiscal policy can be used to cushion the effects of future economic crises. Since major crises happen frequently, prudence suggests that the target should be achieved before the decade is out.

- Tax increases harm economic performance, so elimination of public spending that does not provide enough benefits to offset this damage should be the first step in reducing deficits and debt. This will require undertaking comprehensive value-for-money assessments to identify wasteful spending.

- Post-conference analysis found that achieving this prudent debt target would require increasing the combined federal-provincial primary balance by 1.4 percent of GDP, or $43 billion, starting in 2025/26. This amount includes a buffer – ensuring an 80 percent probability of meeting the debt target – to account for inevitable economic downturns, other crises that raise deficits and debt, and the uncertainty posed by fluctuating interest rates on financing costs.

- The conference was one of four on deficits and debt held in Canada over the past 40 years. A clear and consistent message from these conferences – which politicians have yet to fully absorb – is that debt has economic costs and, therefore, imposes a burden on future generations. In this Commentary, the authors report on, and offer their analysis of, the findings of the latest conference.

Introduction

Does Canada have a debt problem? The answer from a recent C.D. Howe Institute conference is a resounding “yes.” Canada’s public debt should be about 10 percentage points of GDP lower to ensure sustainability. Given that major crises, which put upward pressure on deficits and debt, happen frequently, this target should be achieved before the decade is out.

The May 2024 conference was one of four on deficits and debt held in Canada over the past 40 years. Each aimed to provide guidance to policymakers on managing deficits and debt. While a common thread was concern about the economic cost of public debt, each conference provided context-specific policy advice.

The first conference, “Deficits: How Big and How Bad?” (Conklin and Courchene 1983), occurred when debt levels were rising rapidly but still relatively low. The key policy issue then was whether fiscal consolidation or expansion to support the economy was appropriate.

In the 1994 conference, “Deficit Reduction – What Pain, What Gain?” (Robson and Scarth 1994), and the 2002 conference, “Is the Debt War Over?” (Ragan and Watson 2004), there were clear recommendations to reduce debt levels. In 1994, this was motivated by concerns over economic damage caused by debt approaching 100 percent of GDP and questions about fiscal sustainability. By 2002, although the debt ratio had fallen substantially, further debt reduction was still advocated to reduce the burden on future generations who will not benefit from the spending.

A combination of discretionary measures and sustained economic growth led to a substantial reduction in the combined federal-provincial debt ratio from 2002 until the global financial crisis of 2007-2009. The debt ratio stabilized at a relatively high level after the crisis until the pandemic. The massive increase in debt during the pandemic and subsequent government spending raised the overall federal-provincial net debt ratio to about 75 percent of GDP, nearing levels from the time of the “Debt War” conference. This surge, combined with concerns about further increases, refocused attention on debt sustainability. This concern was reflected in the May conference, “Does Canada Have a Debt Problem?”, which recommended a debt target based on the need for fiscal prudence.

The latest conference included sessions on the economic costs of debt, the sustainability of federal debt, guidance for policymakers on a prudent and fair debt target, and reforming the federal fiscal framework. However, given the one-day format, not all issues could be thoroughly addressed. This report not only summarizes the proceedings but also fills some gaps by providing additional analysis to complement the presenters’ advice.

Economic Costs of Public Debt

Interest expenses were central to the analysis by University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe of the economic costs of public debt. Interest paid on the public debt is often considered a transfer among individuals with no real impact on the economy. However, higher interest payments for a given level of program spending necessitate higher taxes, which harm economic performance by affecting incentives to work, save and invest. If not financed by tax increases, higher interest payments will crowd out valued program spending.

When discussing the opportunity cost of interest payments – the benefits of lower tax rates or higher program spending – Tombe cited work by Dahlby and Ferede (2022). They estimate the economic cost of raising an extra dollar of tax revenue, referred to as the “marginal cost of public funds” (MCPF). The MCPF includes both the dollar taken from the private sector and the loss in output per dollar of tax revenue raised due to reduced incentives to work, save and invest. Higher taxes shrink the tax base not only because of reduced economic activity but also due to efforts to reduce taxable income without changing economic behaviour.

Dahlby and Ferede (2022) find a very high cost from raising taxes. For the corporate income tax, the federal MCPF in 2021 was approximately two.1The MCPF from raising the top federal personal income tax rate has been higher than its corporate tax counterpart since 2012, when the corporate tax rate was reduced to 15 percent. The gap increased in 2016 when the top federal marginal personal income tax rate increased to 33 percent, pushing the MCPF to about 2.9.

The federal government expects to pay $54.1 billion in public debt charges in the current fiscal year. The economic cost of these payments is substantial. If the opportunity cost of these payments is lower corporate income taxes, their economic cost would also be about $54 billion. If their opportunity cost is a lower top personal income tax rate, their economic cost would exceed $100 billion. If the contribution from corporate income and top personal income tax were equal, the economic cost would be about $75 billion.

Other costs of public debt arise from a reduction in the national savings rate, which is the sum of public and private sector savings rates. Government deficits represent public sector dissaving, so with a constant private savings rate, national savings will decline when governments run deficits. Tombe highlighted the impact of lower national savings on investment, presenting data showing a negative correlation between debt ratios and investment ratios across countries (Figure 1). He stated there is “probably” a causal relationship between higher debt ratios and lower investment ratios.

Although Tombe did not elaborate, there are reasons to be circumspect about asserting causality. One reason is that the private savings rate may rise in response to budget deficits if economic agents anticipate higher future taxes to service the debt. Households might increase savings in anticipation, partially offsetting the decline in national savings. There is evidence that expansionary fiscal policy is partially offset by increased household savings. Johnson (2004) concluded that household savings would increase by 30-50 percent of the increase in government debt. In a recent study of fiscal expansions in the Euro area from 1999 to 2019, Checherita-Westphal and Stechert (2021) found that 19 percent of a fiscal stimulus is offset by higher household savings in the short-term, rising to 41 percent in the long-term.

Another reason for being cautious about inferring causality is that in an open economy, a decline in national savings does not necessarily lead to lower domestic investment, as any shortfall can be offset by borrowing from abroad. However, interest payments on borrowed funds and the return on foreign-owned capital reduce national income. An additional cost arises because the resulting current account deterioration must be offset by higher net exports, which requires a reduction in real wages in the export sector.

To complement Tombe’s analysis, we present an estimate of the economic cost of reduced national savings. In a closed economy with constant household savings, a budget deficit leads to a dollar-for-dollar crowding out of investment. Using historical returns on capital and assuming that national savings decline by 60 percent of the deficit due to offsetting increases in household savings, the $1,372 billion in federal net debt in the current fiscal year would have an economic cost of about $90 billion.2 This calculation does not capture the impact of lower capital intensity on productivity, so it underestimates the true cost.

If foreign savings offset the decline in national savings and foreigners invest directly in Canada, they receive the return on this capital, so the gross economic cost remains the same. However, the return is subject to corporate income tax, so the net economic cost would be about 25 percent lower. If Canadian firms borrow abroad to finance domestic investment, the economic cost is the interest paid to foreigners. While gross interest payments to foreigners will be less than the return on capital unless there is a large country-risk premium, interest payments are taxed more lightly.3 Therefore, the net economic cost may not differ substantially.

An additional cost of accessing foreign savings arises because higher capital servicing charges put downward pressure on the current account balance, which must be offset by an increase in net exports. In a small economy, export and import prices are determined in world markets, so the increase in net exports requires a decline in real wages in the export sector. However, if a country’s exports have unique features, increased supply can lower export prices, adding to the economic cost of borrowing from abroad (Burgess 1996).

Calculating the economic cost of investment crowding out when foreign borrowing is possible as the net-of-tax return on capital paid to foreigners establishes a minimum cost because it excludes the reductions in real wages required to increase net exports. The minimum cost would, therefore, be 0.75 x $90 billion = $68 billion, where the $90 billion reflects the economic cost of lower investment, adjusted by a factor of 0.75 to represent corporate income taxes on the returns paid to foreign investors. The $75 billion cost associated with raising taxes to finance higher federal interest expenses does not change with the availability of foreign financing, so the overall cost of the federal debt is approximately $142 billion, or 4.7 percent of GDP in 2024/25.

A similar calculation can be performed for overall provincial debt. In 2021/22, provincial net debt amounted to $784.7 billion, with debt service charges of $30.6 billion. Using the same weighted average economic cost of taxation as for the federal government, the economic cost of provincial debt service charges was $42 billion. The cost of investment crowding out adds another $39 billion, bringing the total cost of debt at the provincial level to $81 billion, or 3.2 percent of GDP in 2021/22. Assuming provincial debt remains at the same percentage of GDP from 2021/22 to 2024/25, the overall cost of Canada’s debt is about 8 percent of GDP.

Benefits of Debt and Its Optimal Level

Tombe also discussed the benefits of public debt, noting its role in financing long-lived assets, stabilizing the economy and smoothing tax rates over time. Governments should borrow to finance investments that will benefit future generations and should finance current expenditures out of current taxes. Spending on education, health and knowledge creation raises special concerns because it benefits both current and future generations. However, since each generation must make these investments, financing them through current revenues typically aligns with the benefit principle.

Counter-cyclical fiscal policy enhances social well-being by mitigating costly deviations from full employment. Additionally, governments can reduce the harmful effects of distortionary taxes by keeping them stable. Since the efficiency cost of taxes is higher when rates are above average than when rates are below average,4 governments should set tax rates at levels sufficient to support expected spending over the cycle and allow deficits to rise and fall in response to unexpected expenditures.5

An issue absent from discussions at the conference was the role of public debt in addressing market imperfections, which can improve efficiency. One such imperfection is the lack of adequate insurance markets against individual-specific wage income losses. As a result, individuals “self-insure” by increasing savings, which is more costly than paying the premiums in a well-functioning insurance market. Public debt puts upward pressure on interest rates and provides a safe savings instrument, allowing households to reduce their savings closer to the efficient level.

Unlike the efficiency gains from using public debt to stabilize the economy and smooth tax rates, mitigating the impact of inadequate insurance markets may justify a permanent increase in public debt. With a well-functioning insurance market, the optimal public debt ratio would be negative – governments should be net savers rather than net debtors. This would allow governments to finance expenditures from interest received on assets rather than from distortionary taxes.6

Empirical issues raised by the inadequate insurance-market approach include whether correcting the market failure is sufficient to make the optimal debt ratio positive and whether the penalty for deviating from the optimal ratio is significant enough to affect the choice of a debt target. Early analyses of incomplete markets found a positive optimal debt ratio. For instance, Aiyagari and McGrattan (1998) calculated an optimal debt ratio of 66 percent of GDP for the US economy. However, Peterman and Sager (2018), using a model with many of the same features as Aiyagari and McGrattan but incorporating multiple generations with standard life cycles instead of a single generation with an infinite life span, found that net government saving is optimal in the US economy. The main reason for the different result is that individuals in a life-cycle model spend a substantial fraction of their working lives accumulating enough savings to make self-insurance possible, so the benefit from self-insurance is smaller than if infinite life spans are assumed.

These results are less relevant for Canada for two reasons. First, employment insurance and other income support measures are more generous in Canada, so self-insurance leading to excess saving is less of an issue. Second, the US analysis assumes deficits are financed entirely by domestic savings, which is a much less realistic assumption for Canada. Foreign borrowing reduces the optimal debt ratio because it lessens the upward pressure on interest rates, which diminishes the impact of public debt on “self-insurance” savings and raises the cost of debt. James and Karam (2001) modified the Aiyagari and McGrattan model to allow borrowing from abroad, which changes the optimal debt ratio from 66 percent to about -80 percent. This qualitative result – that access to foreign savings reduces the optimal debt ratio – has been confirmed by other researchers (Nakajima and Takahashi 2017; Okamoto 2024; and Cozzi 2022).

This review suggests that the inadequate-markets approach does not reverse the conclusion from standard models that the optimal debt ratio is negative, implying that welfare gains can be realized when debt levels are reduced. However, the studies reviewed indicate that the penalty for deviating from the optimal debt ratio is small. In three of the six optimal debt studies reviewed, it is possible to compare the estimated economic costs. In the Peterman/Sager and Nakajima/Takahashi studies, a one-percentage-point increase in the debt ratio reduces consumption by .003 percent. The corresponding figure in the Cozzi study is much higher, approximately .02 percent. These estimates are very low relative to the estimates presented earlier, which imply a loss of .05 percent per percentage-point increase in the debt ratio.

It seems likely that these models are substantially understating the cost of debt. The benefits would have to be understated by an even larger percentage to overturn the conclusion that governments should be creditors not debtors. Since the argument for incurring debt to improve market efficiency is weak, the debt ratio should be chosen by considering only its impact on generational fairness. However, since debt is one of several factors affecting generational transfers, debt policy may have to deviate from the benefit principle to achieve a desired balance of the well-being of current and future generations.

Sustainability Analysis

High debt also raises concerns about its prudence or sustainability: can the interest expense be financed without requiring tax increases or cuts in program spending in the future? In his presentation, Alex Laurin, the Institute’s Vice President and Director of Research, challenged the federal budget’s claim that federal public finances are sustainable (Canada 2024, 382). The federal government’s sustainability claim is based on long-term projections showing a continuously declining debt-to-GDP ratio, reaching nine percent by 2055/56. Moreover, this trend holds even with less optimistic assumptions about interest rates and economic growth.

Laurin argued that this projection is not a convincing demonstration of sustainability for three reasons:

1) Interest Rate Assumptions: In the base case, the effective interest rate on federal debt (r) remains below the growth rate of the economy (g) for 32 years, which puts continuous downward pressure on the debt ratio. This assumption is inconsistent with the historical record. Over the past 35 and 45 years ending in 2022/23, averages of r-g are positive, at 0.8 and 0.4 percentage points, respectively. Only when the averaging period is extended back to include the high-inflation period starting in the 1970s does the multi-year average turn negative.7

2) Program Spending Assumptions: While revenues are assumed to grow in line with GDP, program spending decreases by about one percentage point of GDP over the projection period, causing the primary surplus to rise and putting downward pressure on the debt ratio. A more realistic “no policy change” assumption would keep the share of program spending roughly constant, allowing an assessment of the sustainability of current spending levels.

3) Exclusion of Economic Downturns: The projection fails to explicitly include economic downturns. Over the last 60 years, Canada has experienced five recessions, each prompting discretionary temporary stimulus measures that permanently increased debt. The policy response averaged 1.09 percentage points of potential GDP for each percentage point deviation from potential GDP (Table 1).

Laurin presented an alternative debt projection, assuming that overall program spending grows in line with GDP from 2029/30 to 2055/56 and that r equals g on average over the projection period.8 With these changes, the decline in the federal debt ratio is less pronounced, reaching 29 percent in 2055/56 compared to 9 percent in the budget projection.

Economic downturns were included in the projection by simulating 1,000 random probabilistic scenarios – assuming the frequency and magnitude of recessions over the past 60 years are representative of the future. Laurin assessed debt sustainability by calculating the probability that the debt ratio remains at or falls below its initial value over the projection period.9 The simulations showed an even chance that the debt ratio will exceed its 2028/29 value late in the projection period. Under the International Monetary Fund’s classification (IMF 2022), Canada’s federal debt would be considered unsustainable.

Some conference participants suggested that Laurin’s analysis might not fully capture the risks associated with the federal fiscal position because it assesses a single r-g profile. They also emphasized the importance of including provincial and territorial governments in any sustainability analysis, as these levels are most affected by demographic aging.

For this report, Laurin modified his approach to include provincial and territorial governments’ net debt and to capture the risks of r-g deviating from its assumed zero average over the long term. He introduced variability in the interest-rate growth-rate gap based on historical data, allowing for a more comprehensive risk assessment (methods and assumptions are provided in Appendix).

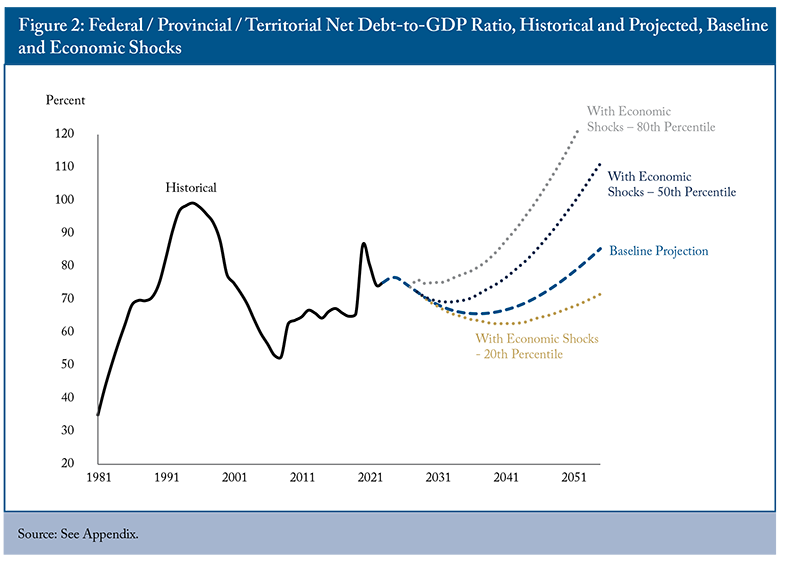

The modified analysis showed that, without any simulated shocks, the combined federal and provincial/territorial net debt-to-GDP ratio initially declines and then stabilizes until 2041/42, when rising healthcare costs due to demographic aging – and the associated interest on provincial debt – cause it to rise steadily (Figure 2, black dashed line). Introducing interest rate and recession shocks significantly alters the outlook, indicating a 50 percent chance that the debt ratio will begin its long-term rise in 2035/36, eventually surpassing 100 percent of GDP (black dotted line). There is a 20 percent chance (the 80th percentile) that the debt ratio will not decrease substantially from its current level and start a steady increase in 2033/34 (grey dotted line). Conversely, there is only a 20 percent chance (the 20th percentile) that the ratio will stay below its near-term value for the entire projection period (gold dotted line).

A Prudent and Fair Target

Prudence

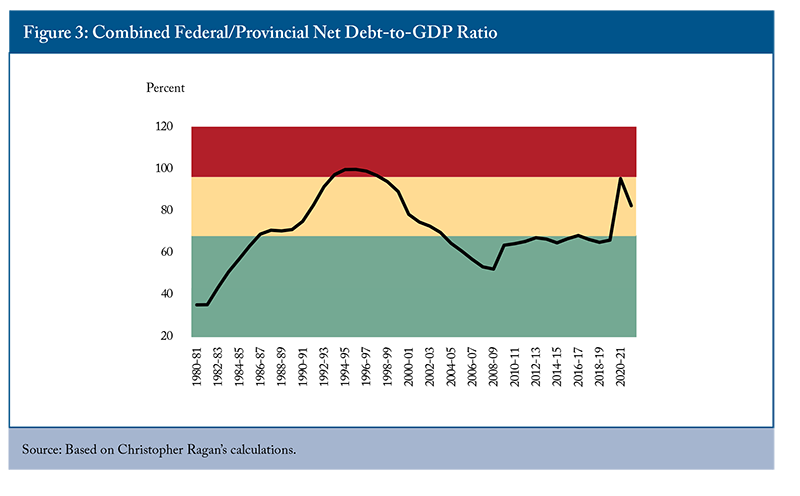

According to McGill economist Christopher Ragan, the main concern about Canada’s high public debt is that it will reduce our ability to borrow to address the next economic crisis. He analysed this issue using three zones for the debt ratio: red (top), yellow (middle) and green (bottom) (Figure 3). The red (top) zone, which represents unsustainable debt, starts roughly five percentage points below the 1995 federal-provincial debt ratio’s peak of 100 percent, when Canada entered a period of “forced austerity.” This entry point to the red (top) zone is higher than the 90 percent threshold for negative effects on growth developed by Reinhart and Rogoff (2010). However, the threshold would be lower if the interest rate on public debt (r) were higher than the rate of economic growth (g).

Ragan argued that the current combined federal-provincial debt-to-GDP ratio is in the yellow (middle) “cautionary” zone. The height of this zone is determined by the buffer required to avoid being pushed into the red (top) zone by an economic crisis. Entering the red (top) zone would mean sharply higher interest rates and lower growth.

To avoid this, Ragan set the buffer at 28 percentage points of GDP, about a quarter more than the increase in the debt ratio during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the frequency of economic crises, he advocated returning to the green (bottom) zone by 2029/30, nine years after the end of the pandemic-induced recession. This requires reducing the federal-provincial debt ratio by about 10 percentage points.

Laurin followed up by determining the fiscal effort required to return to the green (bottom) zone with high probability. His calculations show that, starting in the next fiscal year (2025/26), the combined federal-provincial primary balance would need to increase permanently by 1.38 percent of GDP – or $42.9 billion in 2025/26.10 If implemented through spending reductions, provincial spending would have to decline by about 7 percent, or federal spending would have to fall by almost 9 percent. Note that such spending reductions would still not fully return the combined federal-provincial program spending/GDP ratio to its pre-pandemic 2018/19 value. The federal government could achieve the same effect by raising the GST to 8.5 percent. However, since most spending pressures from an aging population are on provincial governments, it would be sound policy for the federal government to transfer tax points to provincial governments (Kim and Dougherty 2020). Even with near-term fiscal adjustment, additional consolidation may be necessary in the future to prevent a rise in the debt/GDP ratio.

Ragan favoured achieving the debt target through expenditure restraint rather than raising taxes, which he thinks may have reached their limit. Restraining expenditures will be particularly challenging given medium-term pressures from an aging society, rising military and security needs, and potentially increased public investments for the transition to a green economy. Canada, therefore, needs an ongoing and thorough program review to identify low-priority spending.

Fairness

Financing current government spending with debt is generally considered fair if the debt-to-GDP ratio is constant or declining over time, implying that future generations can receive the same level of government services without facing higher tax rates. However, stable tax rates alone are insufficient to prevent intergenerational transfers. Taxes must increase to finance the interest on the debt or remain higher than they would be otherwise. If the tax increase applies to both current and future generations, tax rates would be stable but higher than they would be without the increased debt. The higher tax rates required to finance debt interest and the deficit-induced reduction in national-savings transfer part of the cost of government spending to future generations who do not benefit from the spending.

Assessing generational fairness requires understanding the extent of intergenerational transfers resulting from fiscal policy. The presentation by Parisa Mahboubi, a Senior Policy Analyst at the Institute, offered insights into this issue using generational accounts. These accounts show lifetime net taxes imposed by federal and provincial governments for each birth cohort from 1923 to 2023 and for a composite future generation consisting of all persons born after 2023. The lifetime tax burdens of the 2023 birth cohort and future generations are comparable because a complete life cycle is captured in both cases. Her analysis shows that future generations are expected to face a slightly higher lifetime net tax burden than the youngest living generation.

Preparing generational accounts requires information on lifetime taxes and transfers for each birth cohort alive today and for future generations. Projected values of taxes paid by current birth cohorts are developed based on age-specific profiles of different types of taxes,11 assuming unchanged tax policies. Spending on health, education, elderly benefits, child benefits, social assistance and GST credits vary by age, while other government expenditures are evenly distributed per capita. Per capita taxes, transfers and expenditures are assumed to grow at the same rate as productivity.

The lifetime net tax burdens for currently alive birth cohorts are calculated as the present value of projected tax payments less the present value of projected government transfers the cohort will receive. Lifetime net tax burdens of future generations are calculated using the “no free lunch” constraint: someone, sometime, must pay for all that the government spends (US Congressional Budget Office 1995). The lifetime net tax burden of future generations equals the amount of future spending not paid by currently alive generations.12

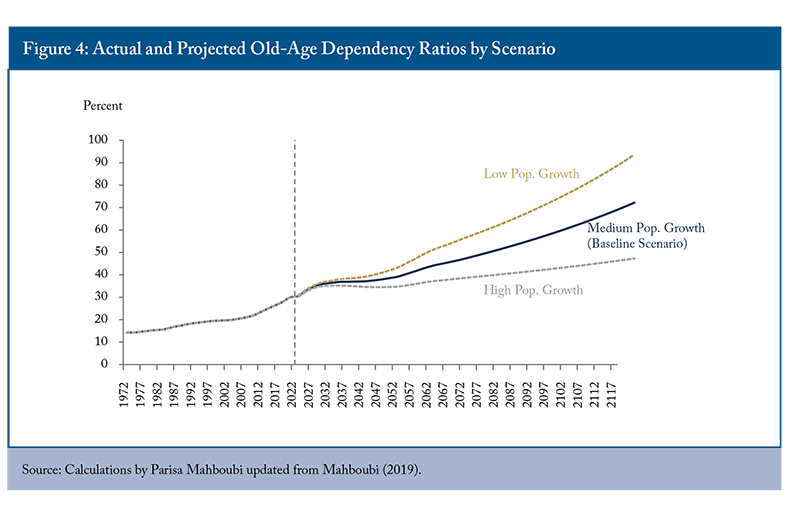

In the baseline scenario, productivity grows 0.94 percent annually, the average GDP per capita growth from 2002 to 2022. The discount rate is the average return on real return bonds over the same period, 1.3 percent.13 Statistics Canada’s medium-growth scenario14 is used for demographic projections, with population growing at an average annual rate of 0.85 percent over the 100-year projection, driven entirely by net immigration. The ratio of those over 65 to those aged 18-65 – the old-age dependency ratio – more than doubles over the projection period, rising from 30 percent to 72 percent (Figure 4).

The increase in the old-age dependency ratio drives upward trends in elderly benefits and health-related expenditures as a share of GDP. Other categories of age-specific spending remain roughly constant.

In the baseline scenario, the lifetime net tax burden of future generations (“unborn”) exceeds that of the cohort born in 2023 (“newborn”) by $23,000 per person (Figure 5). Factors influencing this result include:15

- Fiscal Position in the Base Year: In 2023, federal and provincial tax revenues exceeded program spending by over one percent of GDP. A smaller primary surplus would have decreased the lifetime net tax burden of the newly born, increasing the burden on the unborn.

- Population Growth: Faster population growth reduces the relative tax burden on future generations by slowing the rise in the old-age dependency ratio and reducing the per-capita burden of existing debt.

- Healthcare Costs: If real healthcare costs increase faster than productivity growth, the recently born will pay a smaller share, leaving more for future generations.

The baseline assumptions represent the midpoint of a range of plausible values. While results are sensitive to changes in assumptions, the baseline is considered the most likely outcome. The generational accounts, therefore, suggest that fiscal policy is generationally fair.

However, other factors must be considered when assessing fairness:

- Population Stability: If there were no net population growth, the tax burden on future generations would be much higher, even if the old-age dependency ratio did not change, because the cost of existing debt would be spread over a smaller population. This observation draws attention to the fact that future generations will be paying for services they did not receive, even with stable lifetime net taxes.

- Income Growth: Future generations will likely be richer due to productivity growth, which could justify asking them to bear some costs of current consumption. However, parents may not wish to pass on costs to their children, even if incomes are rising over time. Population growth through immigration substantially reduces intergenerational linkages, which could encourage the current generation to increase the target size of intergenerational transfers.

- New Spending Pressures: The generational accounts do not capture new pressures like rising military and security commitments or higher spending to achieve a net-zero emissions economy. In both cases, underspending in the past has pushed costs into the future. Pre-funding some of this spending by increasing taxes in the near term would even out contributions across generations.

- Comparisons with Near Term Future Generations: Generational accounts compare a representative future generation with the most recent birth cohort. Comparing the tax burden of living generations with the burden on near-term future generations is also relevant.

While the generational accounts indicate that the federal-provincial fiscal stance is fair to future generations under current assumptions, it is beneficial to supplement this analysis with assessments over shorter time horizons. For example, virtually all living generations benefited from the debt-financed income stabilization and health measures implemented during the pandemic-induced recession. There is a strong fairness argument for paying down pandemic-related debt before the next generation starts working and paying taxes, which would occur over the 2035-to-2045 period (Lester 2021).

Federal and provincial Covid-related spending amounted to approximately $430 billion from 2020/21 to 2022/23.16 Federal and provincial debt was $2,092 million in 2022/23. Reducing the level of debt to $1,660 million no later than 2045/46 would be fair to generations born in 2019 and later. However, in Laurin’s prudent scenario, in which debt is sustainable with 80 percent probability, the level of debt rises continuously over the projection period. The gap between the prudent and fair level of debt is $1,200 million in 2035/36. Achieving a fair level of debt would require more fiscal consolidation than is needed to achieve sustainability.

Reforming Expenditure Management

Ragan’s debt target and the recommendation to achieve it through expenditure restraint raise two issues:

1) Building Consensus: How to build a consensus on the proposed debt target and increase the likelihood of achieving it.

2) Identifying Savings: How to identify programs that don’t provide enough value to justify raising taxes to finance them.

Economist and C.D. Howe Institute Fellow-in-Residence John Lester emphasized that achieving a political consensus on a more prudent fiscal approach requires vigorous and sustained advocacy. Part of this advocacy involves convincing governments to surrender some policy flexibility to increase the odds of achieving the target reduction in debt and reduce the risk of relapse after the next crisis.

Lester and Laurin (2023) propose a principles-based fiscal governance framework intended to reduce the bias toward deficit financing in both good times and bad. Governments should adopt guiding principles for fiscal policy, set operational rules for achieving target outcomes and transparently assess consistency with these principles.

At the conference, Lester expanded upon one element of the governance framework: a binding multi-year ceiling on non-cyclical spending. A key motivation for this proposal is the failure to adhere to spending tracks set out in budgets and fiscal updates. For example, in the federal government’s 2019 Economic and Fiscal Update, program spending was projected to decline as a share of GDP, reaching 13.8 percent by 2024/25. The spending ratio projected for 2024/25 increased in successive budgets so that in 2024-25 it will be almost 2 percentage points higher than projected in 2019.18

Binding multi-year expenditure ceilings apply in 11 OECD member countries (Moretti, Keller, and Majercak 2023).19 In the Netherlands and Switzerland, the ceilings are set out in legislation that constrains expenditure growth. Alberta has recently adopted a similar approach.20 However, in most countries, expenditure ceilings are set by the government to ensure consistency with its self-defined fiscal objectives, which may or may not include expenditure restraint. This is the general approach recommended for Canada, although the hope is that the self-defined objective will be to achieve the debt target through expenditure restraint.

The expenditure ceiling would be binding for five years, ideally developed in the first year of a new electoral mandate after a campaign outlining spending plans in detail. The ceiling would cover all categories of spending directly affected by policy decisions. It would be updated annually to account for forecasting errors in program determinants (e.g., inflation, population growth). There would be escape clauses for major economic recessions, natural disasters and war. The ceiling could include a reserve for new policy initiatives, but in the context of expenditure restraint new initiatives may need to be funded by eliminating or modifying existing programs.

Identifying the programs that should be scaled back or eliminated because they don’t provide enough benefits to justify raising taxes to finance them requires, according to Lester, an overhaul of the way the government manages its spending, particularly the performance management framework that is key to establishing value for money. Yves Giroux set the stage for this discussion by describing the federal government’s current expenditure management system.

The requirement to evaluate programs was formalized following the creation of the Office of the Comptroller General in 1978. Despite several modifications, program evaluations have not been successful in affecting strategic spending decisions. The Ministerial Task Force on Program Review (the Nielsen Task Force) from 1984 to 1986 described evaluations as “generally useless and inadequate for the work of program review” (quoted in Grady and Phidd 1993). More recently, McDavid et al. (2018, 302) conclude that evaluations do not “address questions that would be asked as cabinet decision-makers choose among programs and policies.”

Under the current evaluation policy, federal government departments have considerable flexibility in conducting evaluations. They may focus on design and delivery, program beneficiary responses or a comparison of program costs and benefits. A review of 48 evaluations prepared since 2020 in eight departments21 found that only four went beyond assessing operational efficiency and impacts on beneficiaries to examine whether the program represented value for taxpayer money. Three of these applied formal benefit-cost analysis, which is the standard for assessing regulatory proposals.22

Evaluating programs in terms of operational efficiency and beneficiary impacts helps improve programs, but if evaluations are to inform strategic spending decisions, value-for-money assessments must be mandatory. These assessments should be based on the benefit-cost framework applied to regulatory proposals.

Benefit-cost analysis of regulatory proposals – and by extension, spending programs – assesses the overall social benefits and costs of policy initiatives. The quantitative analysis attempts to determine if the economic pie is larger or smaller after government intervention. For example, economic development programs (business subsidies) are implemented with the expectation that they will increase overall real income. To assess this, benefit-cost analysis considers not only the additional investment and employment resulting from the subsidy but also the opportunity cost of workers and capital – the amount that would have been earned otherwise. The net increase in the economic pie is the incremental earnings of workers and capital less efficiency losses from raising taxes or issuing debt to finance the subsidy and resources used to administer and apply for it.

The nature of the assessment should vary by program type. Business subsidies, labour market development programs and climate change mitigation/adaptation measures have benefits and costs measurable in monetary terms. These programs could be ranked by their net social benefits, allowing comparisons within and across program categories. Programs where benefits are less than costs would be candidates for elimination or modification.

A more nuanced approach is needed when assessing social programs and other measures with a fairness goal for several reasons. Their economic impact is ambiguous, and a negative economic impact is not a sufficient reason to eliminate a program. In addition, support for an income redistribution program depends on who benefits from it. As a result, evaluations of social programs should be more descriptive than prescriptive. They should present information on the economic impacts of measures, their fiscal cost, including administration expenses, and a discussion of who benefits from the program and how they benefit. Evaluations should also assess how the program fits into other measures providing support to the target population. This information will allow elected officials and, since all evaluations would be made public, Canadians, generally, to form an evidence-based opinion on the value for money of social programs.

A thorough assessment of government programs through a value-for-money lens may not identify enough wasteful spending to achieve deficit and debt targets. If so, tax increases should be used to achieve the objectives.

Adopting and achieving the debt target will require a political commitment that currently does not exist. The task for policy analysts is to help build a consensus on a more prudent approach to fiscal policy and a revamped expenditure management system. According to Lester, this consensus should be ratified by legislation setting out general principles for sound fiscal policy, supplemented with non-legislated operational rules to guide annual policy and monitor progress. This approach would impose discipline on fiscal policy while allowing flexibility to address unexpected developments. Legislation would strengthen the consensus on fiscal prudence and help prevent backsliding by future politicians.

Conclusion

The evidence presented at the conference confirmed that Canada has a debt problem. Existing debt levels are not prudent, and they raise concerns about generational fairness. Prudence requires that Canada’s public debt be reduced by about 10 percentage points of GDP before the decade’s end. This would require increasing the combined federal-provincial primary balance by 1.4 percent of GDP, or $43 billion, starting in 2025/26.

Tax increases harm economic performance, so elimination of public spending that does not provide enough benefits to offset this damage should be the first step in reducing deficits and debt. Identifying wasteful spending will require comprehensive value-for-money assessments. Governments must not take the easy way out by implementing across-the-board spending cuts. Successful expenditure restraint will also require setting binding multi-year expenditure ceilings to prevent governments from spending revenue windfalls or from increasing spending to improve chances of electoral success.

Canada’s public debt is imposing a burden on future generations. A comparison of the lifetime tax burden on the recently born with distant future generations reveals only a small generational transfer in favour of the recently born. However, burden shifting is much larger from currently living generations to persons born shortly after the pandemic-induced recession. The $430 billion in pandemic-related debt should be paid down by the people that benefited from the income stabilization measures. Achieving this fairness objective would require more fiscal consolidation than needed to ensure sustainability of the debt. For the Silo, Alexandre Laurin/John Lester via C.D. Howe Institute.

Appendix: Assumptions and Methods for the Sustainability Analysis

References

Aiyagari, S. Rao, and Ellen R. McGrattan. 1998. “The Optimum Quantity of Debt.” Journal of Monetary Economics 42 (3): 447–69.

Ambler, Steve, and Craig Alexander. 2015. “One Percent? For Real? Insights from Modern Growth Theory about Future Investment Returns.” E-Brief. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. October.

Burgess, David F. 1996. “Fiscal Deficits and Intergenerational Welfare in Almost Small Open Economies.” Canadian Journal of Economics, 885–909.

Canada. 2024. “Budget 2024.” Department of Finance Canada. April.

Checherita-Westphal, Cristina D., and Marcel Stechert. 2021. “Household Saving and Fiscal Policy: Evidence for the Euro Area from a Thick Modelling Perspective.” Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3992188.

Conklin, David, and Thomas Courchene. 1983. “Deficits: How Big and How Bad?” Special Research Report. Toronto: Ontario Economic Council.

Cozzi, Marco. 2022. “Has Public Debt Been Too High in Canada and the US? A Quantitative Assessment.” University of Victoria, Economics. Available at: http://www.uvic.ca/socialsciences/economics/assets/docs/discussion/ddp2007.pdf.

Dahlby, Bev, and Ergete Ferede. 2022. “What Are the Economic Costs of Raising Revenue by the Canadian Federal Government?” Fraser Institute. Available at: https://roam.macewan.ca/items/73cf71a0-209f-4634-91a7-98d019750638/full.

Grady, Patrick, and Richard W. Phidd. 1993. “Budget Envelopes, Policy Making and Accountability.” Government and Competitiveness Project, School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University. http://global-economics.ca/budgetenvelopes.pdf.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2022. “Staff Guidance Note on the Sovereign Risk and Debt Sustainability Framework for Market Access Countries.” 2022–039. IMF Policy Papers.

James, Steven, and Philippe Karam. 2001. “The Role of Government Debt in a World of Incomplete Financial Markets.” Department of Finance, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch.

Jenkins, Glenn, and Chun-Yan Kuo. 2007. “The Economic Opportunity Cost of Capital for Canada-an Empirical Update.” Queen’s Economics Department Working Paper. Available at: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/189409.

Johnson, David. 2004. “Does the Debt Matter?” In Is the Debt War Over, pp. 173–96. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=s4VcGvjVX0MC&oi=fnd&pg=PA173&dq=%E2%80%9CDoes+the+debt+matter%3F%E2%80%9D+&ots=t0fNWzkyoC&sig=TIQrfQbAitqgSIDuHypw_FT6Eeo.

Kim, Junghum, and Sean Dougherty (eds.) 2020. “Adaptability, accountability and sustainability: Intergovernmental fiscal arrangements in Canada,” in Ageing and Fiscal Challenges across Levels of Government, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Lester, John. 2024. “Minding the Purse Strings: Major Reforms Needed to the Federal Government’s Expenditure Management System.” Available at: https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/For%20advance%20release%20EMS%20E-Brief_359.pdf.

Lester, John, and Alexandre Laurin. 2023. “Ottawa Needs a New Approach to Fiscal Policy.” E-Brief 338. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4397967.

Mahboubi, Parisa. 2019. Intergenerational Fairness: Will Our Kids Live Better than We Do? Commentary 529. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. January.

McDavid, Jim, Astrid Brousselle, Robert P. Shepherd, and David Zussman. 2018. “Linking Evaluation and Spending Reviews: Challenges and Prospects.” Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 32 (3): 297–304. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.43176.

Modigliani, Franco. 1983. “Government Deficits, Inflation and Future Generations.” In Deficits: How Big and How Bad, pp. 55–71.

Moretti, Delphine, Anne Keller, and Marco Majercak. 2023. “Medium-Term and Top-down Budgeting in OECD Countries.” OECD Journal on Budgeting 23 (3). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/39425570-en.

Nakajima, Tomoyuki, and Shuhei Takahashi. 2017. “The Optimum Quantity of Debt for Japan.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 46:17–26.

Okamoto, Akira. 2024. “The Optimum Quantity of Debt for an Aging Japan: Welfare and Demographic Dynamics.” The Japanese Economic Review. May. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42973-024-00156-7.

Panizza, Ugo, Richard Varghese, and Yi Huang. 2019. “Public debt and private investment.” Centre for Economic Policy Research. VOXEU Column. December 4.

Peterman, William, and Erick Sager. 2018. “Optimal Public Debt with Life Cycle Motives.” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3187698.

Ragan, Christopher, and William G. Watson. 2004. “Is the Debt War Over?: Dispatches from Canada’s Fiscal Frontline.” Vol. 45. IRPP. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=s4VcGvjVX0MC&oi=fnd&pg=PP11&dq=%22Is+the+debt+war+over%3F%22&ots=t0fNWqoDsw&sig=Q1poOT4AbHtIkx_NVf5GjrcXEtc.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2010. “Growth in a Time of Debt.” American Economic Review 100 (2): 573–78. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.573.

Robson, William, and Parisa Mahboubi. 2024. Another Day Older and Deeper in Debt: The Fiscal Implications of Demographic Change for Ottawa and the Provinces. Commentary 665. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. August.

Robson, William, and William Scarth. 1994. Deficit Reduction – What Pain, What Gain? (Policy Study 23). Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

US Congressional Budget Office. 1995. “Who Pays and When? An Assessment of Generational Accounting.” Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/Genacct.pdf.

(Microsoft)-1.jpg)