We’ve touched on the symbiotic relationship between film and art in the past, such as our comparison between Blade Runner and Barry Lyndon. Let’s take a look at a few other examples. Hope you enjoy the article below and as always, if we have missed any please comment at the bottom of the page.

Art and cinema, two powerful forms of creative expression, often intersect in fascinating ways. Many of the most visually stunning movies, like the examples below, take their cinematographic style from the world of fine art. While fine artworks are only single frames, they are able to convey a sense of movement and story through their composition, perspective, form, color, and style.

For example, dynamic brushwork and lines can create a sense of energy and movement, while color and contrast can evoke emotion and progression in the narrative. Those same creative techniques are used by cinematographers to create unique cinematic experiences that resonate with audiences. And in some cases, a film’s visual inspiration is taken directly from specific fine art pieces rather than an overarching fine art visual style.

For artists, examining how filmmakers have drawn from fine art can help gain insights into how visual elements impact storytelling, convey emotions, and engage audiences, offering a wealth of inspiration and new approaches to consider in their own work.

The Exorcist – A Surreal Dance of Light and Darkness

“The Exorcist,” directed by William Friedkin, is a seminal horror film that tells the chilling tale of a young girl possessed by a demonic entity. This film’s stark and realistic visual style heightens the horror of the supernatural events unfolding on screen. There’s a scene in the film where Father Merrin, played by Max von Sydow, stands in front of the MacNeil residence, a street lamp casting an eerie glow in the foggy night.

Scene from “The Exorcist”: The eerie glow of the streetlamp mirrors Magritte’s paradoxical day and night, setting the stage for a chilling tale of good versus evil.

This iconic scene (also used for the movie poster) pays homage to René Magritte’s “Empire of Light” series. In Empire of Light, each painting in the series features a paradoxical scene where it is simultaneously day and night – the sky is bright and clear as if it’s daytime, while the landscape below is shrouded in the darkness of night, often with a single-lit street lamp. This juxtaposition creates an eerie, dreamlike atmosphere that challenges the viewer’s perception of reality.

Magritte’s signature surrealism style often embodied contrasts and contradictions, combining ordinary objects to create a sense of mystery and intrigue. In “The Exorcist,” the same visual concept was used to create a sense of dread and foreboding, using the bright light from the windows above against the lone streetlamp lit on the dark, desolate street. The use of this visual reference amplifies the film’s underlying theme of the clash between good and evil, light and darkness.

Empire of Light” by René Magritte: A surreal dance of light and darkness that challenges our perception of reality.

William Friedkin, director of the film, commented on that scene during an interview. He said:

“I chose the house to match the Magritte painting. . . I saw [this painting] in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, it’s called Empire of Light by Rene Magritte. I had that in mind, and I chose the house to match the Magritte painting… the streetlamp…the shaft of light.”

Using the same style of juxtaposition as Magritte’s painting helped Friedkin create tension and foreboding seen throughout this film. Whether it’s the contrast of light and dark, old and new, natural and artificial, or any other disparate elements, this technique can be a powerful tool for creating compelling and provocative art.

Also, by referencing a well-known piece of art, “The Exorcist” connects with the audience, adding depth to the film’s visual storytelling. Incorporating references to other works of art can be a way to engage the audience, create a dialogue with other artists, and contributes to the ongoing conversation that is art history.

Inception – A Labyrinth of Dreams and Reality in Visually Stunning Movies

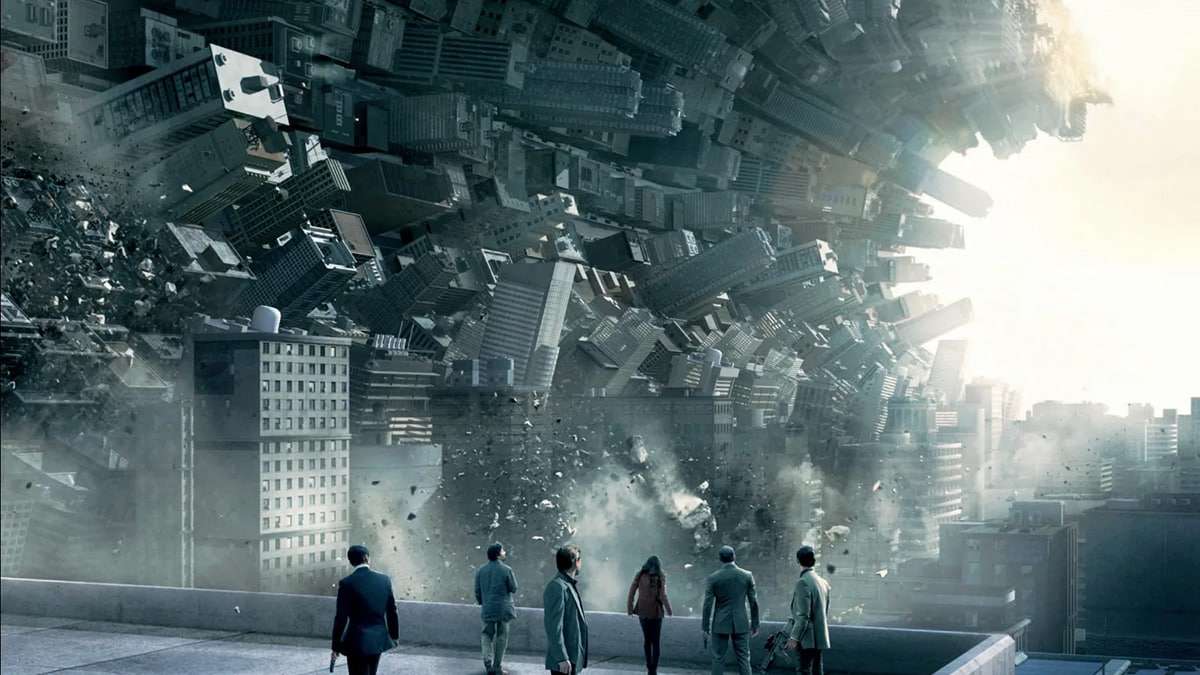

Christopher Nolan’s “Inception” is a mind-bending exploration of dreams and reality. This visually stunning movie is characterized by its complex, surreal architecture and mind-bending visuals that defy the laws of physics. The scene where the dream architects fold the city onto itself is a clear homage to M.C. Escher.

Scene from “Inception”: The city folds onto itself, creating a multi-dimensional dreamscape that echoes the impossible spaces of Escher’s work.

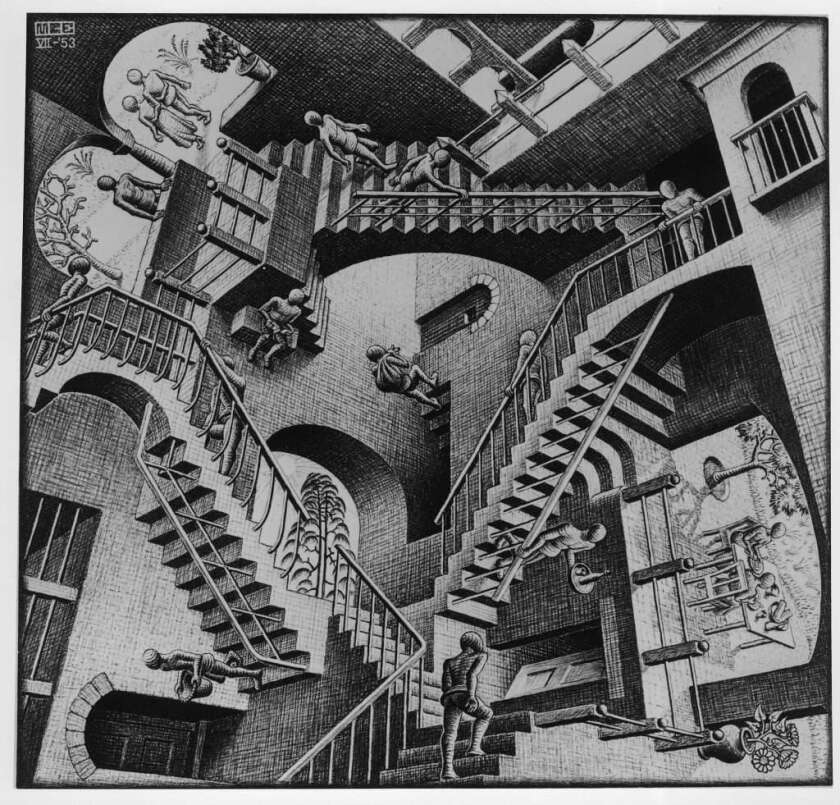

Escher’s work is renowned for exploring impossible spaces and optical illusions, often playing with perspective and gravity to create mind-bending visual paradoxes. “Relativity” is a prime example of this, featuring a labyrinthine structure where staircases ascend and descend in various directions, defying the laws of gravity and normal spatial orientation.

“Relativity” by M.C. Escher: A mind-bending labyrinth of staircases that defy the laws of gravity and spatial orientation.

In Inception, Nolan employs similar visual trickery. The cityscape folds and twists in impossible ways, creating a multi-dimensional space that simultaneously feels possible and impossible. The scene is difficult for our minds to comprehend, much like the world depicted in Relativity. The scene is a visual spectacle and serves the narrative by symbolizing the boundless possibilities within the dream world.

In an interview with “Wired,” Nolan spoke about the influence of paradoxical architecture on the film and stated, “In trying to write a team-based creative process, I wrote the one I know.” Noting that he and his team “liked the idea of exploring paradoxical architecture,” the concept became a key element in the film. The visual correlation between Escher’s “Relativity” and the dream architecture in “Inception” is unmistakable.

For fine artists, the “Inception” and “Relativity” examples offer valuable insights into the power of perspective and the manipulation of space. By referencing “Relativity,” “Inception” brings these impossible spaces to life, creating a visual spectacle that serves the film’s narrative about the malleability of dreams.

Although these surrealist works go to the extreme in manipulating perspective and space, the same idea can be used in non-surrealist works to provide unusual viewpoints, adding a sense of intrigue and dynamism to other traditional art styles.

The impossible, labyrinthine architecture also serves as a visual metaphor for the complexity and unpredictability of the human mind. Artists should consider how visual elements can provide more than aesthetic value or overt narrative context. They can also convey deeper meanings, alternate themes, or subtexts, making the artwork more interesting and evocative.

There Will Be Blood – The Struggle of Man and Nature

Paul Thomas Anderson’s “There Will Be Blood” is a captivating film that delves into the ruthless world of oil drilling in the early 20th century. This beautiful movie’s visual style is stark and gritty, reflecting the harsh realities of its setting and pays homage to the works of Charles Marion Russell.

“Jerked Down” by Charles Marion Russell: A dramatic depiction of the struggle between man and nature in the American West.

Russell’s work often captures the dramatic tension and struggle between man and nature in the American West as exemplified in works like “Jerked Down,” depicting a cowboy being thrown off his horse amidst a thunderstorm – a powerful representation of this struggle. In There Will Be Blood, the scene where an oil derrick catches fire and creates a towering inferno against the barren landscape is reminiscent of Russell’s painting both in style and content.

Scene from “There Will Be Blood”: The towering inferno of the oil derrick, a stark symbol of man’s destructive ambition, mirrors the tension and drama of Russell’s painting.

Both works use light and shadow to heighten the tension and drama of their respective scenes. In “Jerked Down,” Russell uses stark contrasts between the dark stormy sky and the lightning-lit foreground to create a sense of impending danger. Similarly, in “There Will Be Blood,” the scene of the burning oil derrick is dramatically lit, with the fiery glow of the inferno starkly contrasted against the dark, barren landscape. This creates a visually striking image that underscores the danger and destruction caused by something uncontrollable.

Additionally, both works use composition to emphasize the scale and power of nature compared to man. In “Jerked Down,” the cowboy is depicted as small and vulnerable against the vast, stormy landscape, emphasizing the power of the natural elements he is up against. Similarly, in “There Will Be Blood,” the oil derrick, while man-made, is dwarfed by the towering inferno, symbolizing nature’s overwhelming response to man’s intrusion.

These similarities in the use of light, shadow, and composition create a visual link between the two works, suggesting a stylistic influence or at least a shared visual language in their depiction of man’s struggle against nature.

The visual elements create drama and a sense of tension but, more importantly, have a huge impact on the narrative. Depicting a struggle between opposing forces can add a sense of dynamism and narrative to an artwork.

Imagine the same scene in Anderson’s film, but instead of the character being small compared to the fiery event, the main character was in the full frame looking up at the fiery plume, which from that perspective, would be far above in the background of the shot. Such a change would remove the idea of a struggle between forces and minimize the metaphor of the oil derrick representing the protagonist’s destructive ambition.

Melancholia – a Psychological Masterpiece of Beauty and Despair

Lars von Trier’s “Melancholia” explores its characters’ psychological and emotional turmoil against the backdrop of an impending planetary collision. This beautiful movie’s visual style is lush and dreamlike, reflecting the inner worlds of its characters. One of the film’s most memorable scenes is directly inspired by John Everett Millais’ “Ophelia,” a painting that depicts the tragic heroine from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” floating in a stream before her death.

“Ophelia” by John Everett Millais: A serene yet tragic scene that captures the beauty and despair of its titular character.

The painting is renowned for its detailed and emotive depiction of the famous character and for its lush, vibrant colors, intricate details, and sense of serene despair. In Melancholia, von Trier captures a similar mood in the scene where Justine, played by Kirsten Dunst, also floats in a stream surrounded by flowers and foliage. Justine’s floating figure, the serene water, and the surrounding nature all mirror the composition and mood of “Ophelia.” The scene is visually striking and serves the narrative by symbolizing Justine’s despair and resignation in the face of the impending planetary collision.

Scene from “Melancholia”: Justine floats in a stream, her despair and resignation in the face of impending doom mirroring the tragic serenity of Millais’ Ophelia.

The Pre-Raphaelite style that Millais helped pioneer, characterized by its vibrant colors, attention to detail, and emphasis on emotion, is apparent throughout the film, and the visual correlation between this particular scene and the painting is unmistakable.

By referencing Ophelia, Melancholia brings the beauty and tragedy of Earth’s impending doom to life, creating a visual spectacle that serves the film’s narrative about the psychological impact of the event.

The Whispering Wheat Fields of “Days of Heaven”

In the world of beautiful movies, Terrence Malick’s “Days of Heaven” stands as a testament to the power of visual poetry. The film’s imagery, a symphony of natural light and earthy tones, seems to whisper stories of the American heartland, echoing the quiet intensity of Andrew Wyeth’s painting “Christina’s World.”

“Christina’s World” by Andrew Wyeth: A quiet yet intense depiction of solitude and longing in the vast, open landscape.

“Days of Heaven” is a cinematic canvas where the characters are painted against the vast, open landscapes, much like the solitary figure in Wyeth’s work. The characters, dwarfed by their surroundings, become part of the landscape, their stories intertwined with the whispering wheat fields and the ever-changing sky, where humans are but a small part of the larger natural world.

Just as Wyeth captured the subtle play of light and shadow on the grass and Christina’s dress, Malick uses the soft, diffused light of dawn and dusk to paint his scenes, lending them an ethereal, almost dreamlike quality. This masterful use of light enhances the film’s visual appeal and adds depth to its narrative, reflecting the characters’ hopes, dreams, and inevitable disillusionments.

Scene from “Days of Heaven”: The characters, dwarfed by their surroundings, become part of the landscape, their stories whispered by the wheat fields and the ever-changing sky, echoing the quiet intensity of Wyeth’s painting.

The visual language of “Days of Heaven” speaks volumes about its influences. While Malick is a man of few words, letting his films speak for themselves, the cinematographer Nestor Almendros once mentioned that Malick wanted the film to resemble an “old family album.” This desire to capture the past’s fleeting, ephemeral moments resonates strongly with the nostalgic undertones of Wyeth’s work, suggesting a shared artistic vision.

So, what can fine artists glean from this? First, the power of light. Just as Malick and Wyeth used light to infuse their work with a certain mood, artists can experiment with light in their own work to create a specific atmosphere or to highlight certain aspects of their subject. Second, the importance of the environment. “Days of Heaven” and “Christina’s World” shows how the setting can become a character in its own right, influencing the work’s narrative and emotional tone. Artists can think about how the environment interacts with their subjects and how it can be used to convey deeper meanings and themes.

The Enduring Dialogue Between Cinema and Fine Art

The intersection of cinema and fine art is a fascinating exchange that enriches both mediums. As we’ve seen in these examples, beautiful movies like “The Exorcist,” “Inception,” “There Will Be Blood,” “Melancholia,” and “Days of Heaven” have drawn inspiration from fine art masterpieces, creating visually captivating films that audiences will enjoy for decades.

These films demonstrate how the language of fine art – its techniques, motifs, and themes – or its basic principles – such as composition, color, light, and symbolism – can be applied to other mediums to convey emotion, tell stories, and engage audiences.

Ultimately, the dialogue between cinema and fine art is a testament to the power of creativity and the endless possibilities of artistic expression. Whether you’re a filmmaker, a fine artist, or simply an art lover, there’s much to learn and appreciate in this fascinating intersection of art and cinema. For the Silo, Steve Schlackman/artrepreneur.