Found Object, Recycled Art, Readymade or Junk Art?

Abstract

The phenomenon of found objects and waste transmutation into works of art, dominates contemporary African art ostensibly as the new continental creative identity. Majority of contemporary African artists experiment with waste as their preferred artistic medium and find in them (waste), potent metaphors for creative expressionism. However, although this art form is rapidly gaining prominence and international acclaim, it is surrounded by equivocations emanating from available literature sources.

Calixte Dakpogan – between tradition and modernism | AFRICAN CONTEMPORARY ART NOW (wordpress.com)

Discourses have emerged which attempts to theorize this genre of art but such discourses have only created varying levels of ambiguities which impedes understanding of its history, conceptuality and context in contemporary art-space. This article reviews recent literature dealing with found object appropriation in Africa, to expose the obscurities inherent in such studies. Using discourse analysis, this review indicates the existence of ambiguities ranging from terminology devising and classification to issues of hegemonic exclusivity and problems of contextualization. On the premise of these existing gray areas, I propose an in-depth study into this modern African art type, such study should adopt a particularized system to investigate the methodology of African found object art, its ideology and cultural motivation as basic criteria to enable our understanding and establishing of this modern art form as traditional to Africa in form, content and context and subsequently differentiate it from those of European art conventions to which it is currently erroneously likened to.

Keywords: Found Object, Readymade, Ambiguity, Junk Art, Upcycling, Surrealistic Object, Bricolage.

1. Introduction

Incorporation of materials from pop culture into African visual practice may have existed since the continent’s encounter with the west during slave trade and even earlier, as evidenced in the use of European spirit bottles assembled to build deities and shrines (Shiner 1994). But very little is found in literature that provides an account of any in-depth investigation into the historiography of this African art convention. This art genre (waste and found objects appropriation) has proliferated across the entire continent and now dominates contemporary art practice. As observed by Sylla and Bertelsen (1998), “found object art dominates modern African visual practice and very few are those who have not practice found object appropriation art in the continent”.

Numerous reasons are responsible for the fast propagation of this art type and subsequent adoption of ‘bricolage’ creative methodology by African artists, but the most noticeable factor is globalisation (Shiner 1994, Sylla & Mertelsen 1998). While through 21 st century advances in technology and innovations the world is becoming a global village, it conversely leads to increased consumption and accompanying generation of varieties of waste. These waste and found materials occasioned by modernity, become materials for artistic use (Kart 2009). Modern waste (the bye products of modernity and civilization) are employed by Africans as effective visual metaphors for creative explorations and expressionism. This interconnectivity between globalization, modernity and waste generation, accompanied by technological advancements in contemporary Africa, results in waste uniquely adapted into art to a high level it has even been argued that, discarded objects incorporation into art originated from Africa. Evans (2010, p.1) posited that, “through found object transformation, African artists have created a truly unique art form and have bequeathed a new art context to the world”. Reasons being that, for many contemporary African artists trained in western art education systems and equipped with such artistic conceptualism, interrogating the rich meanings locked in waste and found objects is considered quintessential for artistic self expressionism and creation of heighten multifarious layers of meanings since according to Aniakor (2013), “images and objects are plaited with meanings and only by interrogating them, that knowledge is extended and certain messages and ideologies expressed”. Thus, such artists tailor their creative experimentations towards achieving artistic self expressionism and higher codified meanings. This is because as observed by O.Connor, found object artworks are believed to be enriched with superlative double fluidity of meaning (Op cit 2013).

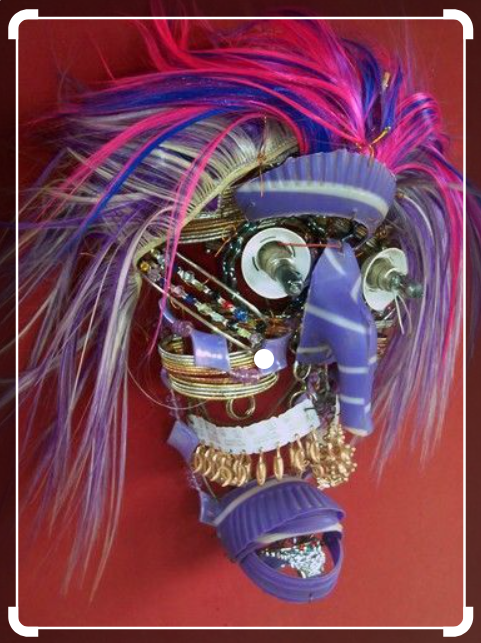

Mamiwata, 2006 Calixte Dakpogan

It is perhaps achieving that fluidity of meaning which has driven modern African artists to position themselves as material experimentalist to creatively interrogate waste and found objects, exploring their artistic qualities and meanings, as well as using such works to reflect societal circumstances and issues in contemporary Africa, as the basis for their art. They do so because, according to Fontaine (2010, p57), “by engaging with ready-mades from pop culture, the artist becomes an agency through which the inherent beauty and art qualities trapped in found/waste materials are brought to lime light via transmutation”.

From an African

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.12, 2013 42 trajectory, not just the beauty in waste is considered but the circumstances creating these waste (globalization, modernity and consumption) forms the ideological/conceptual framework for waste transformation into new art conventions. Whilst this genre of art is gaining prominence and widespread international recognition, it has stirred up scholarly interest from both African/western art historians and critics. Available literature with regards to this contemporary African art form, consist of numerous ambiguities which impedes understanding of its contextual artistic existence. Such literatures have sprang up in the 21st century by scholars [African and western] who, ignoring the historiography of this African art form, only problematically treat found object transmutation into art in Africa as a recent artistic endeavour.

A lot of hasty generalizations and confused contextualizations exist, pointing to the fact that no in-depth research has been conducted to provide clarity to existing gaps in this body of knowledge. Some scholars have struggled with devising a rubric for this art form that will define and categorize it as African. Others have adopted what may be considered a problematic discourse of likening this art form in parallel morphological and ideological terms with European Readymade, Dadaism, Surrealism and Found Object Art, indicating the extent to which scholars have grappled with this subject.

The rubric ‘Recycling in Contemporary African Art’ has been problematically adopted by scholars to holistically describe this African art form in the past two decades, a rubric which Binder (2008) argues that is “misleading”. Binders view point is supported by Van-Dyk who observed that “A lot of artists have made art out of found materials before the word ‘recycle’ was even known in our society… the term Recycling in African Art therefore is a misconception” (Van- Dyk, 2013. P2). This paper reviews recent articles and catalogues which deals with waste transmutation into art, in order to reveal the ambiguities surrounding this modern art genre in Africa, it goes further to posit that for proper understanding to be attained, an in-depth research into found object art is exigent.

Providing solutions to these existing gaps is beyond the scope of this paper, however, in the course of this discourse, insights will be provided into ways through which studies can be effectively directed using cultural perspectivalism of particularised methodological investigation which will enable the possible establishing of this contemporary art convention as African in form, content, and context and, distinguish it from those of western art culture.

2. Articles, Submissions and Gray Areas on waste ‘Upcycling’ into contemporary Africa art:

Four literature sources (three papers and a book) are reviewed in this section to bring to lime light gray areas and gaps in the body of knowledge with regards to found object appropriation in contemporary African art.

African Folk Art Recycled Tin Can Turtle Tanzania

2.1 Globalizing East African Culture: From Junk to Jua Kali Art.

By Margaretta Swigert-Gacheru 2011 Swigert-Gacheru’s paper focuses on waste transformation into art practiced in East Africa, using Kenya as case study. The main idea from an economic and innovative view point purported by the author is that, Jua Kali Ingenuity which culminates into Kenyan Junk Art is a contemporary East African renaissance movement which not only defines a unique genre of art, but contributes to boosting the economy through its bricolage productivity. Also, the author pointed out that Jua Kali is the most dynamic contemporary art form in Kenya which exists as a heighten level of creative ingenuity inspired by the presence of global waste/throw-away and poverty (Swigert- Gacheru 2011. P129).

She further observed that, by virtue of its appropriation of global waste, Jua Kali Junk Art bridges the gap between African and western art worlds by creating a global flow through such hybridization which in turn defies the myth of tribal art and primitive order (Swigert-Gacheru 2011. P127). Another submission made by the author is that, through creative resuscitation of discarded materials deposited in East Africa from Europe, Jua Kali Junk Art combines makeshift creativity with entrepreneurship as a strategy for survival (Swigert-Gacheru 2011. P129). Thus, poverty is cited as the motivation for the innovation of Jua Kali Junk Art in Kenya, whilst various artists inspired by economic hardship are listed. Although Swigert-Gacheru presents evidence of how makeshift creativity in the arts can boost the economy of both the artists and the nation, and also brought to lime light the fact that this ingenuity in East Africa was relegated to the background before now by scholars, the authors classification of what constitutes junk and debris is very confusing and especially problematic because this classification is the proviso for her dubbing of this art form as Junk Art.

The author stated that Junk Art is made from electronic garbage and found natural objects, while environmental debris and old clothes are used in installation (Swigert-Gacheru 2011, p. 131). This classification brings about various unanswered questions which subvert this genre of contemporary African art. For instance, can all art made from junk in Africa be classified as Junk Art? How does natural found object like stones, sea shells etc which are not electronic garbage justify their inclusion in the categorisation Junk Art? Or, does the inclusion of discarded materials into an artwork in this case as the author enumerated (old clothes and environmental debris), automatically transform such works into installation art? Is discarded material Upcycling into art, the-same as installation art? By using media as the criterion for devising the rubric ‘Jua Kali Junk Art’, one will assume that all artworks in East Africa or Africa at large made from found, discarded or readymade

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.12, 2013 43 objects will ideally fall into this category (junk art) but this isn’t the case. Castellote (2011) observed that Olu Amoda uses discarded materials and junk which he prefers to call ‘Re-Purpose Materials’, and that his art be looked at as ‘Repurpose Material Art’. One observes that, Olu Amoda and other African artists even though make use of junk, devise different names for their waste materials and refuse that their artworks be called junk art. This is why Swigert-Gacheru’s adoption of the term junk art to generalize found objects transmutations in Kenya is problematic because other waste appropriation artists in Kenya have different names for their waste materials. Furthermore, by using numerous names for waste materials, devised by different artists as the main trust or generic mode of investigation to explore and interrogate this genre of African art, such line of enquiry as adopted by Swigert-Gacheru and other scholars has only lead to different confused classifications. Two issues stand out from Swigert-Gacheru’s study.

Firstly, the fact that the categorization of what constitutes waste and what falls into the typology debris is problematic means the terminology adopted for this art form is equally problematic. From the author’s submissions, it implies that natural objects, old clothes or environmental debris are excluded from the typology Junk art and by virtue of their waste composition, have become installation art. Also, classifying electronic garbage as the material used for making Junk Art, means they can’t be used in installation art by the author’s submission which makes her proposition very confusing. Secondly the author’s problematic waste categorisation culminates in an inability to differentiate junk art from Installation art. We are thus left with a rubric (Junk Art), which doesn’t even encompass all of Kenya’s found object appropriation, neither does it, reflect or encompass found object transmutation practiced elsewhere in East Africa, nor the entire African continent, and submissions which leaves us unaware of the boundaries between this art (Junk Art) and Installation Art. These unanswered questions and issues stated above, indicates the presence of more than a modicum of gray areas and uncertainties in Swigert-Gacheru’s paper.

2.2 Zimbabwe: The Lost and Found Art.

By Knowledge Mushohwe 2012 This article provides peripheral insights into contemporary African found object appropriation and possesses accompanying obscurities. The main purport of the article is the branding of art that utilizes available waste or ready-mades as ‘Found Object Art’, with the author positing that Zimbabwean artists use found object art as a way of finding meaning in thrash to communicate encoded messages. One major assertion made by the author is that, found object works of art are superlative to the more mundane forms of sculptures which are the old conventions. Arguing that, the punctuated coding system within found object art gives such sculptures a contemplative challenging quality which is an edge over traditional forms of sculpture (Mushohwe, 2012. P1). That additive aesthetic edge is born out of the complex creative process which the author describe as ‘Organised Vandalism’, a process which involves displacing old meanings and forms of objects to create and accord them new forms and meanings (Mushohwe, 2012. P1).

Whilst pointing to the fact that, found object art involves re-contextualisation of objects by dislocating them from their original context and locating them in higher realms of artistic existence, the author equally draws ones attention to the fact that its vandalising nature constitutes a cause for concern as critics question the legality of such practice. Most noticeably and ambiguously so too, is the fact that the author describes and associates found object art in Africa to those of western rebellious art movements. He stated that, “the rebel nature of this found object art is traced to Dadaism and its principal exponent is Marcel Duchamp” (Mushohwe, 2012. p2). Such a bold assertion however, is not proven with adequate facts which make it confusing and problematic as will be enunciated in the next paragraph. Although this paper provides some new insights into this genre of contemporary African sculpture, especially by branding it ‘Found Object Art’ and establishing the fact that, because this art form dislocates discarded objects from their original context to a new creative realm, it assumes contemplative/challenging qualities which accord them aesthetic/creative edge over traditional forms of sculpture such as modelled statues, carvings etc, the article notwithstanding, constitutes further ambiguities and raises various questions.

The author’s likening of this African art convention to Dadaism and purporting that Marcel Duchamp is the founder of Dadaism is shrouded in obscurities without sufficient scholarly evidence to support such claims. Firstly, in as much as Duchamp, Ricaba and Man Ray started anti art in America, Duchamp is not the founder of Dadaism.

Dadaism began in Zurich with artist like Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, Jean Arp, etc credited for stemming the process that lead to Dadaism (Hans 1965, Uwe M 1979, Sandqvist 2006). However, Duchamp a pioneer member of anti-art in America originated the ‘Readymade’ which varies from Dadaist Surrealistic objects in various respects. Therefore, his linking of Duchamp’s Readymade and Surrealistic Found Object in same category is problematic. This is because, he implies by such proposition that Duchamp’s Readymade and Surrealist found objects are same art types which from literally evidence is not the case. Duchamp’s Readymade is a conceptual art style arrived at through his disinterested art ideology and experimentation with his ‘Creative Order and Infrathin’ [aesthetics of indifference] emphasizes the intellectual/conceptual content of an artwork over its visual form, to question what defines/constitute art and the entire art institution. Furthermore, such Readymade were unaltered by the artist and only assumed the dignity of art through ‘Dislocated Contextual Description’ (Read 1985, Obalk 2000, Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.12, 2013 45 El Anatsui’s works and practice methodology.

Her main submission is that Anatsui’s works frequently interpreted principally in relation to clothe, should instead be read as conceptual contemporary sculpture, and a localized reading be adopted in discussing his practice of incorporating locally available or sourced materials into his art. The author also argues that the rubric ‘Recycling in Contemporary African Art’ used to describe all modern African art involving material reclamation is misleading. Also, the term Found Object Art is said to be inappropriate and a wrong reflection of Anatsui’s practice and works since the artist himself chooses to refer to his materials and works as “Objects the Environment Yielded” (Binder 2008, p.27). Thus, she refers to Anatsui’s works as ‘Transformations’ instead of Found Object Art on the premise that the term ‘Found Object’ was born to art history of a particular European movement not relating to Africa, so the term ‘Transformation’ is more appropriate and not only signifies ownership but also an elevation of the material form of Anatsui’s art.

Citing Dilomprizulike (The Junk man of Africa) who works with discarded materials and always requires his works whether they are transformed or not to be called ‘Junk’ as an example, Binder argues that although many artists in Africa work with discarded materials, they are dissimilar in many ways thus, the dubbing of this art type “Recycling in Contemporary African Art” is cloaked in misconceptions. Another valid contribution in this paper is the advocating for a ‘Localized Reading’ of discarded material appropriation in modern African art as the most appropriate method of investigation for understanding its individual cultural peculiarities, since studies and categorizations with emphasis on material rather than practice methodology is inadequate. (Binder 2008, p.35)

By proposing a ‘Localized Reading’, the author indicates that dissimilarities exist between African artists practicing found object appropriation and between this African art convention and those of western art cultures. This view is supported by Olu Oguibe who observed that “the found object for Anatsui was not complete in and of itself, but required the transfiguring intervention of human agency in order to be translated into sculptural form thus, his works differ from others” (Oguibe 1998, p.48). This is why Binder proposed a localized reading into individual’s practices to be able to understand this art phenomenon.

What this reiterates is the fact that, the individual/cultural ideology, methodology and motivation behind found object creative manipulation are key to understanding the works produced and determines the way we perceive and appreciate such oeuvres. This is because “ones aesthetic responses are often functions of what one’s beliefs and perceptions about an object are” (Danto 1981. p99). Furthermore, the suggestion for a localized reading into this genre of contemporary African art is one that will provide a possible vantage point towards really understanding its modern art qualities and conceptuality. If a localized methodological reading is adopted perhaps alongside cross cultural comparison, then Binder’s argument that the adopted rubric ‘Recycling in Contemporary African Art’ for this art genre by western and African scholars is ambiguous and misleading will properly be understood and addressed.

This is because, only by understanding the practice methodology, cultural inspiration and ideology upon which these works derive the potency for their artistic being that the point of departure can be established that will lead to a comprehensive understanding as to why this art form may be peculiarly African. This said, propositions in Binder’s article raises a lot of issues that further contribute to the obscurity ubiquitous on this subject matter. The author classifies Anatsui’s artworks as ‘Transformations’ and her decision to adopt this terminology as appropriate for this style of art, hinges on two hypothesis; on the one hand is the fact that the found materials are manipulated creatively and the degree of such manipulation is employed as a vital coefficient and on the other hand, the ideology and intended codified messages locked in the piece to be expressed or communicated to the general public.

This paradigm of thinking though insightful, leads to the following lines of questioning; If the degree of manipulation of the discarded is the basis for devising the rubric and classification ‘Transformation’, how is Anatsui’s works different from Jua Kali Junk Art which adopts even deeper levels of material manipulation? By adopting the degree of artistic manipulation of the discarded as the sine qua non for classification, it is apparent that Anatsui’s assemblages or constructions are not different from Kenyan Junk art nor are they different from those of other Nigerian and African artists who work with found objects. On this premise, can those other works be classified too as Transformations? Or, the other way round, Anatsui’s works as Junk Art? Furthermore, by citing technique of making (Construction) as the basis for differentiating Anatsui’s works from others, does it mean that artworks made with this same technique (Assemblage/Construction) using different materials are or not qualified for this sobriquet Transformations?

Another trajectory in Binder’s investigation is the use of intent/metaphoric content (ideology) behind the works as a criterion and reason for underpinning the exclusive categorization of Anatsui’s works as Transformations. If the conceptuality, and metaphoric content are central to terminology devising for art types, then it becomes very confusing why Anatsui’s art should be treated as exclusive from others nor is there any need for discussing and differentiating found object appropriation in Africa under numerous terminologies by scholars because, almost all African artists who engage in this practice uses their art for same purposes; which according to Peek (2012), “is to create aesthetic objects for appreciation or to comment on the present condition of modern societies”. Issues relating to over consumerism, socio-economic and political ills and cultural/moral decadence are regular Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.12, 2013 46 themes associated with this art genre in Africa, which is equally the conceptual feature in most postcolonial art.

Which is the aesthetics of humanity that engages with the current and transforming state of human race and defined by such extend of engagement with these concerns (Young 2010). As this is the case, based squarely on ideology and messages conveyed like in most post colonial African art, there are no major differences between Anatsui’s art and those of other African artist who work with waste and convey same contemporary concerns in visual form.

Olu Amada “Trois Jeunes Filles”

Conversely, will it then be a misplaced submission, if Anatsui’s art is called Junk or Found Object art? Or can Jua Kali Junk Art or that of Zimbabwe, those of Delomprizulike or the works of Olu Amoda qualify to fall under the typology Transformations? While Binder’s article provides great insights into Anatsui’s practice, as well as pointing out the fact that, attempting to generalize this genre of African art under the rubric ‘Recycling in Contemporary African Art’ as is often the case is misleading, and further observing that, adopting Euro-American terminologies and likening African found object art tradition to those of the west is a faulty proposition, her assertions in this article equally bellies lots of uncertainties observed above which hasn’t help provide clarifications needed on this subject.

3. Ambiguities Identified

This brief survey indicates the presence of gaps in the knowledge and discourse of found object appropriation in modern Africa. Thus, various issues emanating from the reviewed literature sources are categorised into the following problems subheadings:

3.1 Muddle Terminologies and Classification Problem

From the foregoing, it is apparent that the first ambiguity is the problem of classification. Terminologies such as Junk Art, Trash Art, Found Object Art, Recycled Art, Transformations, Readymade, Objects the environment yielded, Re-purpose Material Art, etc have all been adopted by scholars and artists alike to exclusively discuss and describe their art as products of individual ingenuity even though their artworks like those of others, equally involves the use of same creative methodologies and ideologies for waste and found object appropriation from pop culture into art in Africa. This trenchant attempt at carving out a unique individualistic identity or for ethnic groups or gilds working in this modern African art convention as is the main purport in many literary discourses, is an evidence of classification ambiguity which constitutes into grappling with devising or coining a suitable terminology for this art form which will effectively categorize it as individually exclusive or holistically encompassing to accommodate all African art forms made from readymade or found materials into one typology.

3.2 Hegemonic Exclusion of the Historiography of African Found Object Appropriation

There is also the problem of hegemonic exclusion which is made manifest in the writings of western scholars on African contemporary art. In an attempt to co-opt other art traditions into western art mainstreams, these scholars have refused to investigate or make any references to the origin of found object art in Africa and have concentrated in treating this art form as a recent artistic endeavour. In doing so over the years, that is ignoring the historiography of this African art convention, western scholars have fashioned a discourse on African found object transmutation art, which problematically excludes its historic context (origin). The resultant effect is evidenced in the fact that, even African scholars and critics have adopted this paradigm and thus, problematically treats African found object appropriation as simply an extension of European modernism rather than an art form with any cultural particularities/inspirations or determined by traditional philosophies.

So long as this remains the case and the origin of this art convention in Africa hegemonically excluded from contemporary discourse, the ambiguities surrounding it will continue to impede any comprehensive understanding of its contemporary artistic existence.

3.3 Problem of Contextualization

“There has been much debate surrounding the applicability of Euro-American terminology and classification to systems of art production outside of that specific history. While I am in no way arguing that these terms are not also applicable to practices other than those in Europe and America, I am suggesting a considered application rather than a catch-all grouping of the work as either recycling or found object. The answer is to acknowledge the local while assessing the reciprocity of art practices in a global historical context” (Binder 2008, p36) Binder’s argument is on the premise that, Euro-American terminologies may not effectively reflect or apply to art traditions or styles that fall outside the specific history which generated such terminologies.

If this happens, that is, Euro-American terminologies applied to outside art traditions, it will deprive such art forms or traditions drawn into European art mainstreams, of their true cultural artistic value, identity and conceptuality. Binder’s observation exhibits another level of ambiguity surrounding found object appropriation art in Africa as equally observed in the studies surveyed earlier in this paper, which is the problem of contextualization. Most writers both African and western, have applied Euro-American terminologies to describe this genre of art and in the process contextualize it based on western art movements of the 1900s like Readymade, Found Object, Dadaism etc. This application has not proven to be exceptionally adequate because, the ideological and conceptual frameworks that gave birth to those art forms and movements in the west are not responsible for the innovation.

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.12, 2013 47 of this modern African art form. This means that such Euro-American terminologies cannot effectively reflect and encompass this art type in Africa. Other writers have invented terminologies to treat this art type as uniquely African yet they fall into the pit fall of making references to and likening this African art convention to western terminologies/theories and modernists art movements attempting to justify their course, but in the process, do not provide enough evidence to establish why this art form is uniquely African and different from those of the west. Such multifarious terminology devising and faulty contextualization for exclusivity purposes by these scholars and artists end up excluding others in the continent who work in same style convention and beclouding their art practices in ambiguities.

This problem exists because contemporary African artists and critics as well as their western counterparts have consciously and continuously engaged in the discourse of treating found object art in Africa as a very recent artistic endeavor and have avoided any trace of history to establish the origin of this African art form. If an in-depth research into the origin and growth of found object art in Africa is conducted, then the problem of contextualization of this art genre will be addressed.

4 Conclusion

Whilst found object appropriation into art in Africa has become the core of almost all contemporary creative experimentation, artist’s inventions of numerous rubrics to describe their materials in unison with some African and western scholars, has lead to problematic and obscured submissions. Such problematic propositions as this paper illustrates, has created various levels of obscurities (muddle terminologies/classification problem, problem of western hegemonic exclusion of the historiography of this art form in Africa and the problem of contextualization) which impedes understanding of this modern art convention.

Available literature sources reviewed in this discourse which contextualizes this art type in analogous aesthetic context with European art movements are misleading, while those that treat it as traditional to Africa provide insufficient information to underpin their assertions. Conversely, it is my opinion that for clarity to be attained, an in-depth research into found object transmutation into art in Africa is exigent. The point of departure firstly for such investigation will be to examine the origin and history of found object art in Africa. If the origin is established, it will determine if this art convention is inspired by traditional culture or occasioned by western influences.

Furthermore, such study should adopt a particularized reading system to examine the practice methodologies of African found object appropriation artists, the ideologies and cultural motivations behind this art convention. If a particularized reading is conducted into these three key aspects of African found object art, both the colonial, cultural and contemporary context of waste and found object appropriation into African art will be accorded much needed clarity and the problem of contextualization addressed. If this is done, it will effectively establish it (found object and waste appropriation genre of art in the continent), as African in form, content and context as well as differentiate it from European art movements/art cultures for which it is currently erroneously likened to. Providing solutions to these ambiguities is beyond the scope of this investigation.

Rather, what I have done is simply bringing to lime light the various obscurities surrounding this modern art type and suggesting directions for further investigations. For the Silo, Clement Emeka Akpang, School of Art and Design, University of Bedfordshire, Luton, United Kingdom.

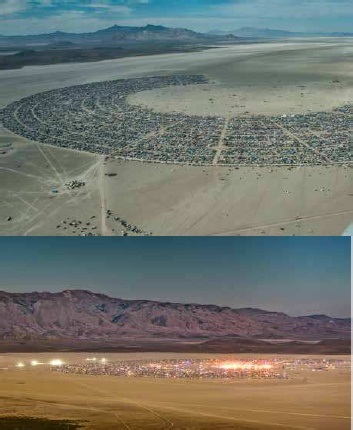

Featured image- Dadaab Refugee Camp :: Behance

References

Adewunmi, A. ed (2008) Art is Everything 7: International Waste-to-art Workshop Catalogue. Nigeria: Timex Press Aniakor, C. (2013) ‘Interrogation of Objects and Images as means for Postgraduate Visual Enquiry in Environmental Sciences’ [Oral Interview]. Cross River University of Technology Calabar-Nigeria. 20th June, 2013 Arthur, D. (1981) The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Breton, A (1938) Surrealist Situation of the Object, in Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. R. Seaver and H. R. Lane Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 272. Breton, A. (1987) Mad Love, trans. Mary Ann Caws. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Binder, L. M. (2008). ‘El Anatsui: Transformations’. African Arts, 41(2), 24-37. Castellote, J (2011) ‘Olu Amoda’ A View From My Corner [Online] Available at: http://jesscastellote.wordpress.com/2011/01/16/olu-amoda/ Accessed on: 10 th June 2013 Emgin, B. (2012) ‘Trashion: The Return of the Disposed’. Design Issues, 28(1), 63-71. Evans, B (2010) ‘Contemporary African Art’ Contemporary African Art Newsletter [Online],

Available at :http://www.contemporary-african-art.com/contemporary-african- art.html#sthash.wGlqQyzZ.dpuf….14 Accessed: 3rd June 2013 Hans, R. (1965), Dada: Art and Anti-art. Oxford: University Press. Iversen, M (2004) ‘Readymade, Found Object, Photograph’ Art Journal Vol. 63, No. 2, pp. 44-57 Kart, S. (2009). ‘The Phenomenon of Récupération at the Dak’Art Biennale’ African Arts, 42(3), 8-9. Mushohwe, K. (2012) ‘Zimbabwe: The Lost and Found Art’. The Herald [Online]

Available at: Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.12, 2013 48 http://www.allafrica.com/stories/201210240435.html?viewall=1 Accessed: 8th April 2013. O’Connor, L., (2013) ‘El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa’ CAA Reviews [Online] p.1-3. Available from: Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), Ipswich. Accessed June 5, 2013. Oguibe, O. (1998). “El Anatsui: Beyond Death and Nothingness,’ African Arts 21(1):48-55. Sandqvist, T. (2006) Dada East: The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire. London: MIT Press Shiner, L. (1994) ‘`Primitive fakes,’ `Tourist Art,’ and the Ideology of Authenticity’, Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism, 52 (2), pp.225. Swigert-Gacheru, M. (2011) ‘Globalizing East African Culture: From Junk to Jua Kali Art’, Perspectives on Global Development & Technology, 10 (1), pp.127-142 Sylla, A., Betelsen, M. (1998) ‘Contemporary African Art: A Multilayered History’, Diogenes, 46 (184), pp.51- 70. Uwe M, S. (1979), George Grosz, His life and work: Universe Books Van Dyk, M. (2013) ‘The Transformer: Mine Hill artist Re-imagines Found Objects as Art’ Daily Report [Online].

Available at: http://www.dailyrecord.com/article/20130509/GRASSROOTS/305090005/The- transformer-Mine-Hill-artist-re-imagines-found-objects-art?nclick_check=1 Accessed on: 29 th August, 2013 Young R. J. C. (2010) Explorations – What do we mean by Postcolonial Art [Video]. Edinburgh: British Council. Available Online At: http://vimeo.com/15559912 Accessed: 5th June 2013.