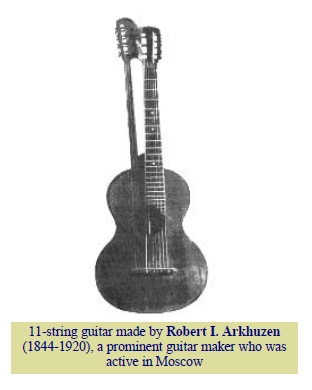

Russian music life in all periods, having very old origins. But only recently has this guitar world started opening to western Europe, and we still know far too little about Russian composers for guitar and Russian guitarists. It was quite difficult for me to get information about some Russian guitarists, due both to the ever-present difficulties in communication (it is still difficult just to send a fax to Moscow during the day time)and to the problems of language comprehension.

Russian music life in all periods, having very old origins. But only recently has this guitar world started opening to western Europe, and we still know far too little about Russian composers for guitar and Russian guitarists. It was quite difficult for me to get information about some Russian guitarists, due both to the ever-present difficulties in communication (it is still difficult just to send a fax to Moscow during the day time)and to the problems of language comprehension.The guitar was not the only known plucked instrument in Russia; two other instruments at least are worthy of mention: the domra and the balalaika. The domra is nowadays known in two variants with three or four metallic strings and in different sizes. It has a triangular shape, is tuned by fourths,and is played by means of a plectrum.

It is the most ancient plucked instrument, having been imported by the Mongols during the 13th century. Its tremolo is similar to the one of the Neapolitan mandolin and its range is large, due to its having 16 frets up to the junction of the neck. It is now employed both as a solo instrument and in an orchestra,together with the balalaika .