Run a search for “Octapad” or “Octapadist,” and you’ll find a vast musical community. Learn how the instrument became a household word.

Run a Google search for “Octapad” or “Octapadist,” and you’ll find a vast musical community. The overwhelming majority of these players have two fundamental traits in common. They use a device with eight rubber pads, and they likely live in a specific geographic location. But more on that in a moment.

An International Debut

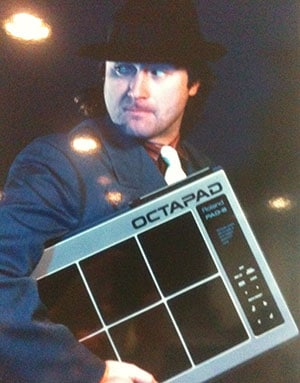

When the Octapad Pad-8 debuted in 1985, it was a solution for artists looking to add MIDI to live performance. 1989’s Octapad II Pad-80 delivered enhanced patch capabilities and memory storage.

Fans could see the instrument on global stages with Phil Collins, Eric Clapton, New Order, and UB40. Soon, the SPD line arrived—with the bonus of onboard sounds—and the Octapad name all but disappeared.

A Specific Niche

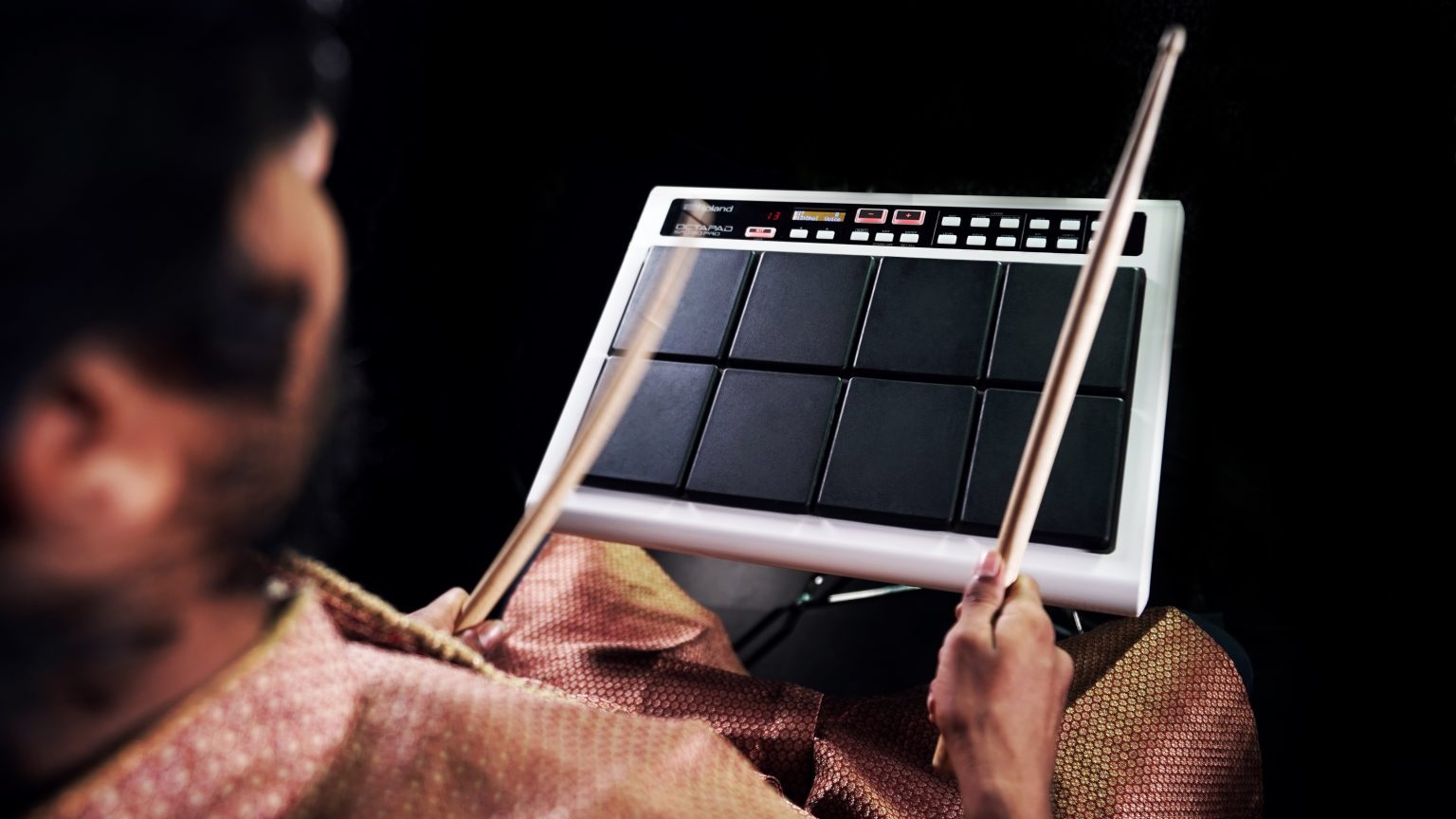

In 2010, with the SPD-30, the Octapad returned in a big way. Still, in one populous, musically-rich region, it never went away. Thanks to a mutable layout and portable design, the Octapad captured a specific niche in India. It remains the instrument of choice for devotional musicians and Bollywood players alike.

Today, artists like Priya Shiyara Flash Octapadist and Mayuranga Octapadist maintain Facebook profiles. They represent the tip of the social media iceberg. Octapadists with large followings appear all over YouTube, sharing skills and growing audiences at the same time.

Traditional Tones to YouTube

Take Jiten Sunil Kriplani. He’s a popular YouTuber with almost a million subscribers who goes by the name Janny Dholi. “I’ve been using the Octapad for many years,” Sunil Kriplani says. “I absolutely love the true and dynamic tones which are customized especially for Indian artists. It’s the best for live shows and recording sessions.”

It was over 20 years ago that the original SPD-20 took the world—and especially India—by storm. Nowadays, legions of Indian musicians embrace the Octapad as their primary instrument. SPD-20 sounds permeate Bollywood, folk, devotional, and other musical styles across India.

A Practical Tool

Musical Director Tushar Deval says, “I’ve been working in this industry for almost thirty-five years. It was 1998 or 2000 that I first tried the SPD-20, and I have been using it ever since. Great experiences come from different places.”

For Deval, the speed of creation is part of what cements the Octapad in India’s professional music world. “Making patches in SPD-20 is so easy,” he explains. “Basically, any Hindi song comes on, and we can make five of them in ten to fifteen minutes.”

“Great experiences come from different places. Any Hindi song comes on, and we can make five of them in ten to fifteen minutes.”

-Tushar Deval

The 808 of India?

With such broad appeal, it’s easy to think of the Octapad as the TR-808 of India, so far-reaching is the instrument’s influence. The original eight-pad layout—much like the 808’s drum pads—is iconic. Like the 808, the Octapad’s look is instantly recognizable.

The instrument’s latest incarnation, the SPD-20 PRO, expands on the Octapad’s legacy. Among a host of sounds, it includes the following: dholak (a two-headed hand drum with drumheads attached by ropes), mridangam (a principal rhythmic accompaniment drum for Carnatic performances), kanjira (a frame drum from the tambourine family), ghatam (one of India’s most ancient percussion instruments), the duggi (an Indian kettle drum played with the fingers and palm).

“The addition of 200 kits is mind-blowing,” Sunil Kriplani says of the upgraded Octapad. “It’s my favorite feature.”

Based in Pune, Maharashtra, Ajay Artre has used the Octapad for over six years. He appreciates the instrument’s core tones and interface. Artre praises “the sounds, editing, and especially the display.”

Roland’s history boasts many instruments intended for one use that became unexpected legends for something else entirely. Initially, an accompaniment device, the TB-303 kickstarted the acid house movement. Of course, the ultimate example of this trend, the TR-808, is inexorably linked to hip-hop’s history.

An Unusual Path

By contrast, the Octapad’s ascension from MIDI device to the go-to Indian devotional music tool is less clear. It doesn’t produce a sound utterly unlike anything that came before it. Rather, the Octapad plays a practical role in the musical culture of India.

In a blog for Roland India, Rupesh Iyar describes the Octapad as “a passionate instrument to play.” Iyar stresses that “any percussion player can switch to the Octapad from their traditional instrument.”

“It’s a passionate instrument to play. Any percussion player can switch to the Octapad from their traditional instrument.”

-Rupesh Iyar

Therein lies the essence of the Octapad’s popularity in India. The device established its place in the country’s musical culture by bridging the past and the present. Those eight pads help move traditional sounds into the future, one pattern at a time.

Original article by our friends at Roland/ Ari Rosenschein.