Key Canadian trade laws do not refer to national security as a factor that allows Canada to counter threats from imports of goods or services. Given the tense geopolitical situation, I propose ways to close this “national security gap.”

The gap is particularly worrisome in two key import-governing legislation: (1) the Customs Tariff Act and (2) the Export and Import Permits Act.

I will show why the omission of the national security element in these and possibly other statutes needs to be remedied.

National Security & Chinese Exports

The Americans imposed surcharges on Chinese EVs, steel, aluminum, semiconductors and other products in May 2024 in response to heavily subsidized Chinese imports that were said to have breached international trade rules.

The EU started applying countervailing duties on Chinese EVs in July this year, using a more standard trade remedy process to counter the injurious impact of subsidized imports on the European automotive industry.

The danger posed by Chinese EVs, steel and aluminum imports, plus these actions by Canada’s major trading partners, led the Canadian government to apply comparable tariff surcharges. The strategic threat posed by China’s state-subsidized exports made for the right response by Canada.

While existing laws allowed the federal cabinet to take action in this case, it also brought home the fact that there is an absence of any reference to “national security” in some of Canada’s major trade law statutes.

Section 53 – Canada’s Rapid Response Mechanism

In the United States, Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act, along with Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act, authorize the president to increase tariffs on imports if the quantity or circumstances surrounding those imports are deemed to threaten national security.1

Section 232 was used by the Trump administration in 2018 to apply surcharges to a range of imports from numerous countries, including Canada. However, these tariffs were ultimately dropped in the face of threats by Canada to retaliate against American goods exported to Canada.

Unlike the US, Canada lacks the legislative means to impose import surcharges on the basis of national security. The closest we have is Section 53 of the Customs Tariff Act, which focuses on the enforcement of Canada’s rights under trade agreements and responses to practices that negatively affect Canadian trade. It was Section 53 that was used in the August decision on Chinese EVs, etc., referred to earlier.

Indeed, there are similarities between Section 301 of the US Trade Act of 1974 and Section 53 of the Customs Tariff Act.But while existing laws allowed the federal cabinet to act in this case, the case brought home the fact that there is an absence of any reference to “national security” in some of Canada’s major trade law statutes.

Governments have shied away from using Section 53 as a policy tool over the years. It was used only once before its present deployment, in response to the Trump administration’s surcharges on Canadian steel and aluminum in 2018 and 2020.2

The surcharges were ultimately withdrawn when the US tariffs were terminated.Section 53 comes under Division 4 of the Actentitled “Special Measures, Emergency Measures and Safeguards,” giving the government broad powers to apply unilateral tariff measures on the joint recommendation of the ministers of Finance and Global Affairs:

…for the purpose of enforcing Canada’s rights

under a trade agreement in relation to a country

or of responding to acts, policies or practices of

the government of a country that adversely affect,

or lead directly or indirectly to adverse effects on,

trade in goods or services of Canada…

There is no requirement for public consultations or input under this provision. Although the government held a round of stakeholder consultations before moving on Chinese imports in August, it was not legally obliged to do so. While the ministerial recommendations must be fact-based and supported by credible data, the law is effective in that nothing inhibits rapid action by the federal cabinet. In this respect, it is a superior tool to Section 232 of the American legislation.3

The critical shortcoming, on the other hand, is that while allowing the government to protect Canadian trade interests in a fairly rapid fashion, Section 53 does not allow action on imports found to be threatening national security, whether it be economic, military or other. There is clearly a need to repair this omission, not only here but in Canada’s other trade laws.

In my view, we need a national security component in Section 53 as the Canadian counterpart to Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act.

Import Controls and National Security

Together with tariff measures, Canada can control imports under the Export and Import Permits Act(EIPA) through the creation of import (and export) control lists designed to achieve particular strategic, security and economic objectives. These lists are established by orders-in-council,

requiring listed goods and technology to have a permit in order to be imported or exported. These permits are issued by the Trade Controls and Technical Barriers Bureau in Global Affairs Canada (GAC). Without a permit, imports of controlled items are illegal.

While Section 5(1) of EIPA provides for the creation of import control lists covering arms, ammunition and military items, it fails to provide for imports of goods or technology to be controlled for national security reasons. The Act could not have been used, for example, to deal with the effects on national security of imports of Chinese EVs, steel, aluminum or any other goods or technology. EIPA is thus deficient in this regard.

There is a related issue when it comes to export controls. Section 3(1) of EIPA authorizes the establishment of export control lists, among other reasons:

“(a)…to ensure that arms, ammunition,

implements or munitions of war, etc. … otherwise

having a strategic nature or value will not be made

available to any destination where their use might

be detrimental to the security of Canada.”

The reference to the “security of Canada” under paragraph (a) is the only such reference in the statute and is confined to the security aspects of imports of arms, ammunition, munitions of war, etc. While not as significant as the problems regarding import controls, it is nonetheless a serious omission.

The result is that as EIPA is currently drafted, the federal government lacks the legal authority to create import or export controls designed to protect or safeguard Canadian security. EIPA needs to be amended to add this authority on the part of the government.

Indeed, it may be desirable to re-consider much of the architecture of EIPA from the viewpoint of safeguarding Canada’s security interests on both the export and import side.

Controlling Imports Through Sanctions

Canada’s sanctions laws are found in the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act (JVCFOA), the United Nations Act, and, notably, the Special Economic Measures Act (SEMA). Each of these statutes allows the federal cabinet to issue sanctions through regulations

applicable to specific countries and/or jurisdictions and prohibiting transactions in specific items of goods or technology. None of these laws allow sanctions for matters related to Canadian security.

SEMA is Canada’s most widely used sanctions legislation. Section 4 is the only part of the Act that uses the term “security,” but only in instances when, among other matters:

(b) a grave breach of international peace and

security has occurred that has resulted in or is likely

to result in a serious international crisis.

Because of the restrictions on international peace and security, the government lacks the authority to issue sanctions dealing with national security interests.4

For example, Canada’s sanctions on Russia are directed at countering actions that “constitute a grave breach of international peace and security that has resulted or is likely to result in a serious international crisis,” with no reference to Canadian national security interests.

SEMA should be amended to allow prohibitions of any transaction or dealings of any kind where Canada’s national security is at risk.

Trade Remedies and National Security

In accordance with the GATT/WTO Agreement, antidumping and countervailing (AD/CV) duties can be applied to dumped or subsidized imports when a domestic industry is injured or threatened with injury from exactly the same imports as that industry produces. In Canada, these are provided for under the Special Import Measures Act (SIMA).

SIMA actions are driven by complaints filed by domestic producers who make exactly the same or directly competitive products as the imported items. It means, for example, that in the absence of a Canadian industry threatened with injury or actually injured by the same type of Chinese EVs, aluminum or steel imports as those producers make, AD/CV duty remedies would not be available. SIMA makes no reference to national security as a factor in the application of these duties.

In short, because the SIMA process is geared to provide protection to domestic producers and private sector industries, it is inappropriate as a vehicle for dealing with national economic security concerns that range well beyond those private interests.

The same is true in the case of safeguards, another kind of trade action allowed under the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement to counter floods of imports that are not dumped or subsidized but, because of their volume, cause or threaten serious injury to domestic producers of the same product.

In Canada, safeguard measures come under the Canadian International Trade Tribunal Act, where an inquiry takes place and, if recommended by the Tribunal, are applied under the Customs Tariff Act.

As in the case of dumped or subsidized imports, safeguard measures are designed to protect specific domestic industries and not to deal with overarching national security issues.

Again, because the objective of these remedial measures in international and Canadian trade law is to protect a domestic industry from financial harm due to imports and not to deal with broader questions of national security, the absence of reference to “security” in these various statutes does not seem to be a significant issue.

National Security under International Trade Law

Article XXI of the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs & Trade (GATT) is the only provision in the entire WTO package that deals with national security. That article (entitled “Security Exceptions”) allows departures from normal trade rules to permit unilateral trade-restrictive measures that a contracting party “considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests…taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations.”

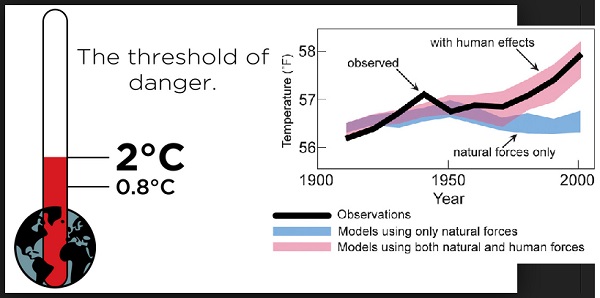

The drafting of GATT Article XXI dates back to the post-World War II Bretton Woods era. What was considered an international emergency at that time was war, regional armed conflict or a global pandemic like the Asian flu of 1918-1920. The same broad view of international emergency conditions was applied when the Uruguay Round negotiations took place (1991-1994) leading to the conclusion of the WTO Agreement.

With recent cataclysmic changes in the world, whatever the WTO-administered multilateral system might prescribe, governments are moving to protect a range of national (and economic) security concerns by means of unilateral measures in ways that were not envisaged when the Bretton Woods architecture was devised in the late 1940s.

For decades, there was little recourse to Article XXI exceptions. However, their use emerged in the last number of years with the unilateral surcharges imposed by Trump.

The situation is different – and materially different – in the case of Chinese exports, not only EVs, steel or aluminum but also in technologically advanced or other critical items. These are goods that, by abundant evidence, are heavily subsidized, with massive overcapacity, exported to global markets as part of the Chinese government’s strategy to enhance its geopolitical position – facts uncovered in the EV situation through detailed investigations by the EU and the US.5

Thus, aggressive actions by China and possibly other countries in strategically sensitive areas take the issue beyond the WTO ruling in the US-Section 232 case and raise these to the level of an “emergency in international relations.”

In summary, the concept of an international emergency is much changed in today’s digitized, cyber-intensified world, including the aggressive and destabilizing policies of Chinese state capitalism and other bad actors. The application of GATT/WTO rules drafted in 1947 and updated in the 1990s must be adapted to deal with today’s realities if they are to provide governments with meaningful recourse.

Conclusions

In conclusion, Canada has a panoply of criminal, investment, intelligence gathering and other laws that address national security concerns. However, there is a notable absence of the term “national security” in Canada’s core trade law statutes.

This absence is of concern in the Customs Tariff Act and the Export and Import Permits Act, two important statutes that give the government authority to act to counter injurious imports threatening Canada’s national security.

Given the state of world affairs and the challenges Canada faces from aggressive players like China, Russia, Iran and others, the omissions in these statutes need to be remedied. This should be acted on immediately. There is also a lack of reference to national security in Canada’s sanctions legislation, notably the Special Economic Measures Act (SEMA), the main Canadian sanctions statute.

Amendments should be made to make security concerns a ground for imposing sanctions here as well. The findings of EU agencies on Chinese BEV after a detailed investigation support the view that Chinese state capitalism and its centrally planned industrial capacity are geared toward dominating world markets in critical goods, part of that country’s geopolitical strategy. These and other similar governmental actions can be said to meet the “emergency in international relations” threshold under the WTO Agreement.

Given the state of affairs at the WTO, including the paralysis of its dispute settlement system, amendments to or reinterpretation of the GATT rules are difficult, if not impossible. The result is that governments will be resorting to unilateral application of the Article XXI exclusion in their own national security measures. While the situation may evolve at the WTO, and without diminishing Canada’s support for the multilateral rules-based system, the federal government should bring forth measures to add reference to national security interests in the above statutes. For the Silo, Lawrence L. Herman/ C.D. Howe Institute.

International Economic Policy Council Members

Co-Chairs: Marta Morgan, Pierre S. Pettigrew Members: Ari Van Assche Stephen Beatty Stuart Bergman Dan Ciuriak Catherine Cobden John Curtis Robert Dimitrieff Rick Ekstein Carolina Gallo Victor Gomez Peter Hall Lawrence Herman Caroline Hughes Jim Keon Jean-Marc Leclerc Meredith Lilly Michael McAdoo Marcella Munro Jeanette Patell Representative, Amazon Canada Joanne Pitkin Rob Stewart Aaron Sydor Daniel Trefle

1 The Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (Pub. L. 87–794, 76 Stat. 872, enacted October 11, 1962, codified at 19 U.S.C. ch. 7); The Trade Act of 1974 (Pub. L. 93–618, 88 Stat. 1978, enacted January 3, 1975, codified at 19 U.S.C. ch. 12).

2 The government announced it was applying these “to encourage a prompt end to the U.S. tariffs, which negatively affect Canadian workers and businesses and threaten to undermine the integrity of the global trading system.” See: “United States Surtax Order (Steel and Aluminum),” Government of Canada, June 28, 2018, https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2018/2018-07-11/html/sordors152-eng.html.

3 Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act allows the president to impose import restrictions – but these must be based on an investigation and affirmative determination by the Department of Commerce that certain imports threaten to impair US national security.

4 The array of Canada’s sanctions can be found on the GAC website at: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/sanctions/current-actuelles.aspx?lang=eng.

5 The EU measures followed a countervailing duty approach, as opposed to direct action in the case of Canada and the US. In its extremely detailed investigation, EU agencies found, on the basis of massive evidence, that:

“ . . . the BEV [battery electric vehicle] industry is thus regarded as a key/strategic industry, whose development is actively pursued by the GOC as a policy objective. The BEV sector is shown to be of paramount importance for the GOC and receives political support for its accelerated development. Including from vital inputs to the end product. On the basis of the policy documents referred to in this section, the Commission concluded that the GOC intervenes in the BEV industry to implement the related policies and interferes with the free play of market forces in the BEV sector, notably by promoting and supporting the sector through various means and key steps in their production and sale.”See: “Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2024/1866,” European Union, July 3, 2024, at para. 253, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2024/1866/oj