[This article was first published by The Silo on April 22, 2014] On June 10, 2009, the Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair, Marie Wilson and Chief Wilton Littlechild were appointed as Commissioners to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), a component of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is unique from other commissions around the world in that its scope is primarily focused on the experiences of children and its research spans more than 150 years (one of the longest durations ever examined). It is also the first court-ordered truth commission to be established and most notable, the survivors themselves set aside 60 million dollars of the compensation they were awarded to help establish the TRC.

Over the course of its 5 year mandate, one of the main tasks of the Commission is to create an accurate and public historical record of the past regarding the policies and operations of the former residential schools, what happened to the children who attended them, and what former employees recall from their experiences.

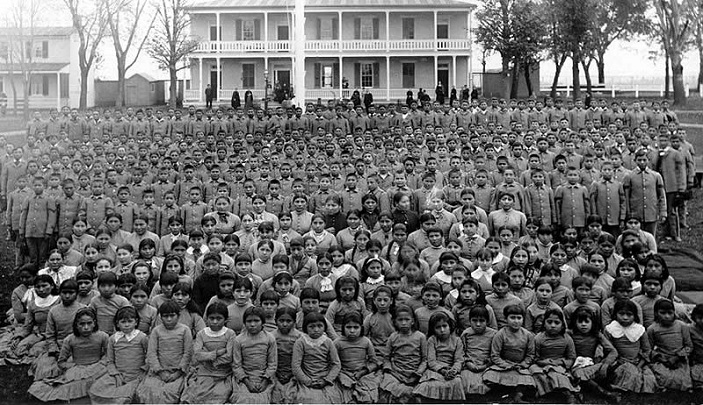

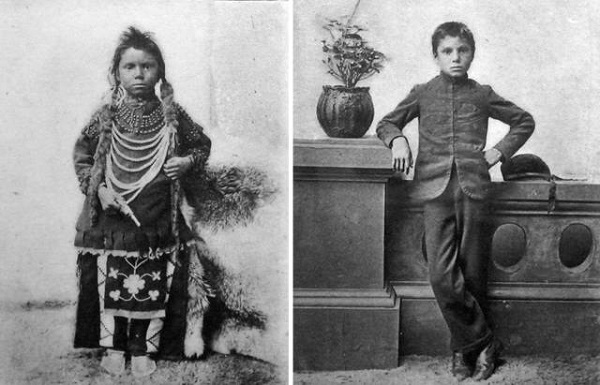

It is difficult for Canadians to accept that the policy behind the government funded, church run schools attempted to “kill the Indian in the child”. The violent underpinnings of the policy challenge the way we think about Canada, and call into question our national character and values. We have been taught to believe that we are a peaceful nation, glorious and free.

The residential school legacy shines a light in our darkest corners, where we feel most vulnerable.

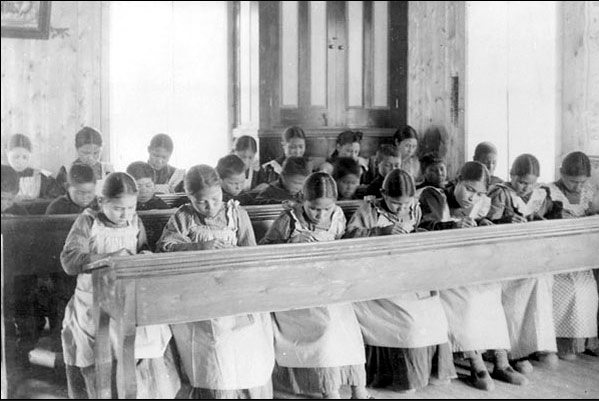

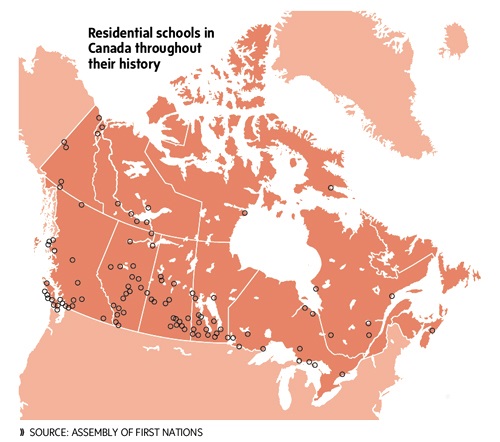

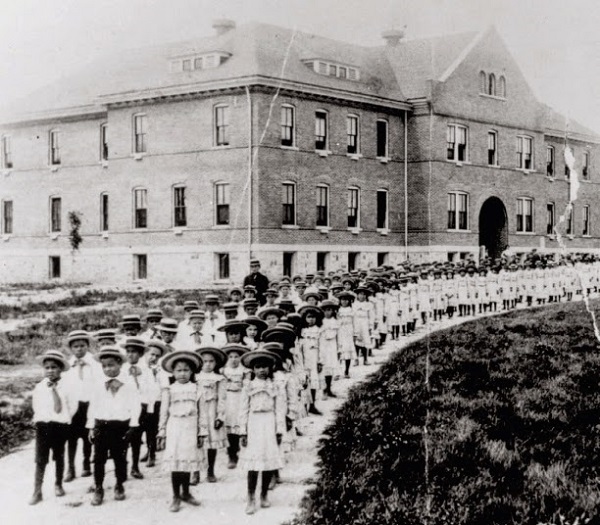

Over 130 Residential Schools were located across Canada, with the last one closing in 1996. More than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children as young as five years old were forcibly removed from their families and placed in institutions that shamed their languages, customs, families, communities, traditions, cultures and history. In essence, they were not allowed be themselves and denied the love and belonging owed to all children.

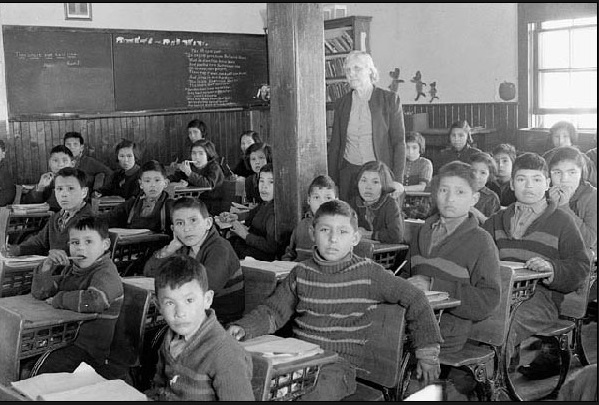

While some former students had positive experiences at residential schools, many suffered emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and others died while attending these schools. Other lessons in trauma included assimilating children to gender roles, non-skilled labour and religion to prepare them for future integration. For the parents left behind, the worst lessons in shame, grief, loss and disconnection. Whole societies were undone.

In addition to creating the public historical record of the past, the survivors also tasked the Commission to reveal to Canadians the full and complete story.

What were they thinking? Why should it matter to ordinary Canadians?

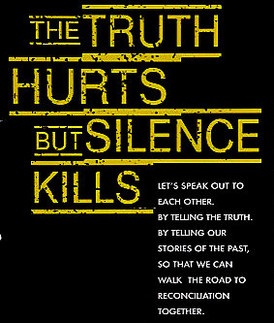

Here’s why: When we tell our stories we change the world. When we don’t tell our stories we miss the opportunity to experience empathy and to cultivate authenticity, joy and belonging. (Brené Brown, 44) Through story-telling, the survivors are compelling Canadians to listen and respond with deep compassion and to re-set relationships in a big way in this country. This is our greatest opportunity to recognize shared history and our shared humanity. These stories are a gift and will help us to shape our shared future.

Through statement gathering at national or regional events and at TRC Community Hearings, former students, their descendants and anyone who has been affected by the Residential Schools legacy, had an opportunity to share their individual experiences in a safe and culturally supportive environment. The TRC concluded its last community hearing in March 2014 and has collected more than 6, 200 statements.

Almost all of them were video-and-audio-recorded and range from a few minutes to a few hours. The statements will be stored at the National Research Centre on Indian Residential Schools at the University of Manitoba. Students, researchers and members of the public will be able to access the statements to learn about residential schools and the legacy they leave behind.

As the TRC begins to reveal to Canadians the full and complete story of residential schools and inspire a process of reconciliation across this country, ordinary Canadians seem ill-equipped to make the journey from shame to empathy. “We know the voices singing, screaming, wanting to be heard- but we don’t hear them because fear and blame muffle the sounds” (Brené Brown, 42) We need to prepare ourselves to go to the dark corners of our history, so we can stand in the light together as equals.

In my next article, I will share with you more about empathy, how to practice empathy and why its essential to building meaningful and trustworthy relationships.) For the Silo, Leslie Cochran.

(Brené Brown, 42 and Brené Brown, 44) are taken from her first book “I thought it was just me.”