Paul Jenkins – The West and a Workable New World Order?

From: Paul Jenkins

To: Global governance observers

Date: May 2, 2024

Re: The West and a Workable New World Order?

One can describe the so-called liberal world order as a set of ideas for organizing world democracies. While openness and trade, rules and institutions, and co-operative security have been the principles that have shaped the liberal order, it also required sovereign nation states to provide the foundation for the creation and development of a system of intergovernmental organizations, or system of global governance.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the system was designed primarily for the advancement, economically and politically, of Europe and the United States. Yet since 1945 the liberal world order has evolved, giving impetus to the steady increase in global economic integration to the benefit of many nations and people.

Advances in science and technology have been critical to the evolution of the liberal order, but there has also been a need for the structures of global governance to evolve and keep pace.

On the economic front, for example, the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, following Richard Nixon’s 1971 decision to abandon the dollar’s link to gold, gave rise to the creation of the G7. And the Asian Crisis of 1999 led to the creation of the G20.

Throughout the entire postwar period, however, tensions inherent between the sovereign authority of the nation-state and the need for collective global governance increasingly challenged the liberal order.

Indeed, the advent of the Cold War led to the liberal world order becoming hegemonic, organized around the economic and political strength of the United States with its dominance of global governance through the various institutions making up the global governance system.

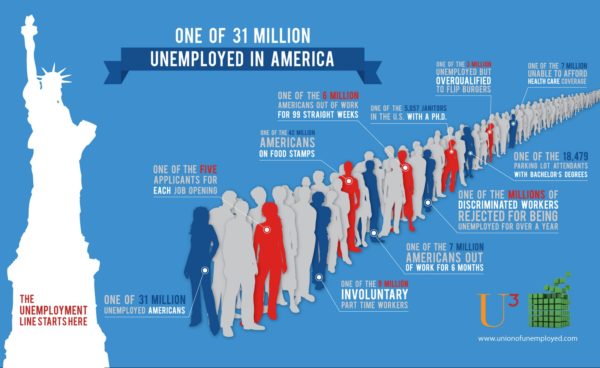

But over the years, pushback took hold. As the benefits of global economic integration spread and the United States was no longer the singular engine of growth, both democratic and autocratic countries found voice and began to resist the principles that shaped the liberal order. Even core nations of the liberal order began to voice their concerns in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis as the market-based financial system failed to self-regulate (as had been advertised), and as the liberal order proved unable to provide social protection for those adversely affected by globalization.

Effectively, a new world order began to unfold, with the resulting slowing and even fragmentation [DS1] [PJ2] of global economic integration.

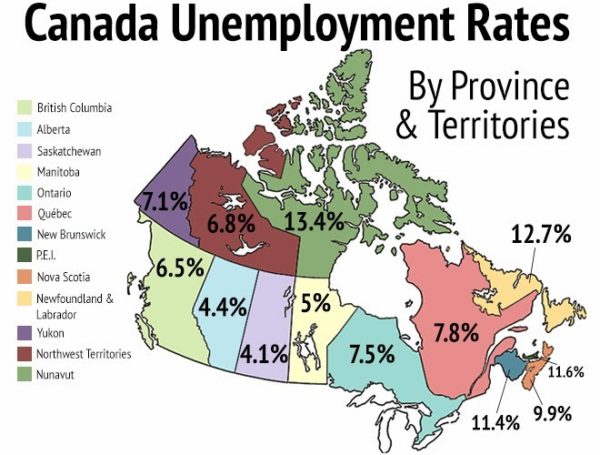

At the same time though, virtually all nations, regardless of regime or stage of development, are facing the same challenges: Financial instabilities, rising inequality, weak productivity growth, climate change, spread of infectious disease, AI, cyber security and on and on.

These vulnerabilities represent global risks that can only be tackled and minimized through collective action. This in turn requires a new world order that treats the world as it is, not how we wish it to be.

What does this mean for the West, and in particular the United States and Canada?

The unique advantages of the United States are its open society, fair and law-based market economy, and allure for talent from around the world. To sustain these advantages, maintaining its wealth and its position as the centre of the free world, it cannot close its doors to further global economic integration.

Geopolitically, what might this look like?

John Ikenberry argues that the answer can be found in the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and non-intervention of the Westphalian system, the 1648 treaties that ended the Thirty Years’ War and established the modern nation state. The key insight of the Westphalian system is that all countries are vulnerable to the same global risks. The leap forward in mindset that is required is the acceptance that states are the rightful political units of legitimate rule.

For the West, and the United States in particular, this implies the need to accept these new realities, and in so doing, the need to work together to build a new world order that preserves their liberal democratic values, and those of its allies, while at the same time recognizing that the economic challenges they face are not unique to them.

The unfolding relationship between the United States and China will define whether we achieve a workable new world order.

The economic incentives are there for this to happen.

For China, the incentive is further progress in closing both its internal income gap as well as the gap between itself and the developed world. The payoff would be setting in place the foundation for a sustained rise in living standards for all its citizens.

For the United States, the incentive is in preserving its strength as an open society and its vision of the world that has considered the interests of others. In many respects, it remains uniquely capable of playing the central role in sustaining the global economic system.

The challenge in re-imagining such a new world order is geopolitical. The task is to renew global governance with today’s realities in sharp focus.

Paul Jenkins. Mister Jenkins is a former senior deputy governor of the Bank of Canada and a senior fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute.

For the Silo,

For the Silo,