By the winter of 1982, we had been going to the Harbourfront Antique market every Sunday for about a year, and were making a pretty good living selling things we had bought at local auctions and garage sales. Then one day, I read in the excellent and entertaining “bible” of Antique dealing “The Furniture Doctor” by George Grotz , that the village of Defoy, Quebec was mecca for the antique picker.

To quote “there’s a wonderful secret wholesale place up in the province of Quebec. It’s the tiny town of Defoy. Only a gravel road from the main highway, but about a half a mile down there is the wonderful “antiques dump” of Rene Boudin and his freres. And here under enormous sheds you will find literally acres of antique furniture, chests, and tables piled three to five pieces high”.

https://goo.gl/maps/ZhW6d7x5Z72G7buz6?coh=178572&entry=tt

The book had been out quite awhile so there was no telling if this situation still existed, so I asked the old guys at the market if they knew of such a place. I got several reports of it’s glory days, followed by “of course that was years ago and nobody goes anymore. That being said they also all encouraged me to give it a go, and gave me “leads” as to who may still be active. We gathered up our courage, our baby, and what cash we had, and set off.

That first twelve hour drive felt like an eternity. It was a tired crew who pulled in late afternoon to a tiny motel in Victoriaville, Quebec.

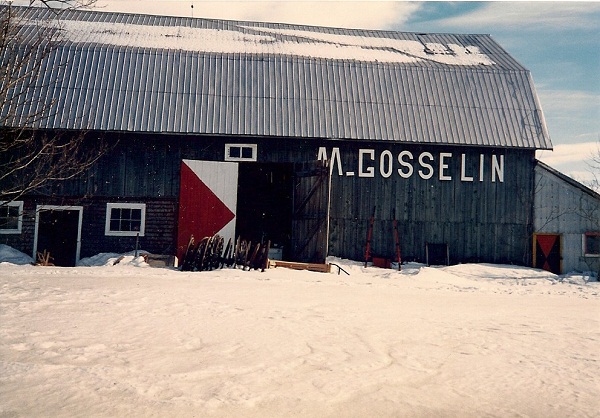

Our first move was to look up Marcel Gosselin in the phone book because he was one of our most promising leads. To our delight he was listed, and he answered and told us where and how to come the next morning. It wasn’t hard to find because it was near town, and his name was painted boldly on the barn. Marcel greeted us warmly and proceeded to lead us to his main barn. There, behind the red and white cross doors was the biggest pile of dining chairs I had ever seen. About thirty feet across it reached to the top of the barn.

Through the hatch work of legs I could see tantalizing glimpses of a cupboard and some chests. Then he took us upstairs where in a loft he had sorted hundreds of chairs in sets of four, six, or more. Some were painted and some varnished. It was $45cdn each for simple painted chairs, $65cdn each for nicer pressbacks and/or varnished ones. We got a couple of sets knowing we would get about $150cdn-$250cdn each for these when refinished., Next I asked him about that cupboard I had seen in the giant pile downstairs. He told me all about it including the age, condition and reasonable price of $250cdn and told me he would extricate it and have it ready for my next trip if I wanted it.

I said I did, and then he didn’t even want a deposit.

“That’s not the way we do it down here. Your word is good enough, until it isn’t. I liked him immediately and knew he was a man I would enjoy doing business with.

Next he took us to the garage attached to his 100 year old frame house. The downstairs was filled with every kind of “smalls” including small boxes, glassware, pottery, antique clothing, folk art, etc, etc; and the tiny, about to collapse, upstairs loft was filled with hundreds of pottery washsets. There were some beauties, and this was a hot item at the time in Toronto. Prices ranged from $45cdn-$75cdn per set. We bought 8 of the nicest sets knowing we would get between $145cdn to $375cdn back home.

This was getting truly exciting.

We spent a terrific four hours or so with Marcel that first day and pulled away from his place, with half our money spent, and half our truck full of interesting, excellent quality, and reasonably priced stuff, not to mention the overwhelming sense of warmth, excitement and wonderment of that first glimpse into a Quebec picker’s life. We were hooked, and we knew it was the first of many more trips to see Marcel. For the Silo, Phil Ross.

Featured image courtesy of tourismecentreduquebec.com