The article below (Furthering the Benefits of Global Economic Integration through

Institution Building: Canada as 2024 Chair of CPTPP) was first published by the C.D. Howe Institute by Paul Jenkins and Mark Kruger.

Introduction

Over the last 10 to 15 years, the global economy has become fragmented. There are many reasons for this fragmentation – both economic and geopolitical. A particularly important factor has been the inability of the institutions that provide the governance framework for international trade and finance to adapt to the changing realities of the global economy.

This erosion is reflected in the cycles of outcome-based measures of globalization, such as trade-to-GDP ratios. Research indicates that the development of institutions that promote global integration is highly correlated with more rapid economic growth. To secure the benefits of economic integration, the international community should re-commit to a set of common rules. This should involve the renewal of existing institutions in line with current economic realities.

But institutional renewal alone is not sufficient. Nurturing and growing new institutions are also critical, especially ones reflecting the realities of today’s global economy. Most promising in this regard is the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

The CPTPP is seen as a “next generation” trade agreement. It takes World Trade Organization (WTO) rules further in several key areas, such as electronic commerce, intellectual property, and state-owned enterprises.

Expansion of CPTPP represents a unique opportunity to strengthen global trade rules, deepen global economic cooperation on trade and sustain an open global trading system. The benefits for Canada of an expanded CPTPP are further diversification of its export markets and deepened ties with countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

Trusted Policy Intelligence

The challenge to enabling broad-based accession to CPTPP is geopolitical, reflecting the rising aspirations of the developing world, the associated

heightened contest between democracy and autocracy, and the prioritization of security. Indeed, for many, today’s security concerns are at the forefront, trumping economic issues. We argue that recognition of the economic benefits

of global economic integration must also remain at the forefront, and that research presented in this paper shows that institutional building is at the core

of securing such benefits.

As 2024 Chair of the CPTPP Commission, Canada has an opportunity to play a leadership role, as it did in the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions 80 years ago, by again promoting global institution building, this time through the successful accession of countries to the CPTPP, both this year and over the long run.

- Cycles in Global Economic Integration

Former US Fed Chair Bernanke points out that the process of global economic integration has been going on for centuries. New technologies have been a major force in linking economies and markets but the process has not been a smooth and steady one. Rather, there have been waves of integration, dis-integration, and re-integration.

Before World War I, the global economy was connected by extensive international trade, investment, and financial flows. Improved transportation – steamships, railways and canals – and communication – international mail and the telegraph – facilitated this “first era of globalization.” The gold standard linked countries financially and promoted currency stability. Trade barriers were reduced by the adoption of standardized customs procedures and trade regulations. The movement of goods, capital, and people was relatively unrestricted.

The outbreak of World War I frayed global economic ties and set the stage for a more fragmented interwar period. The Treaty of Versailles imposed

punitive measures on Germany, exacerbating economic hardships. Protectionist policies, such as high tariffs and competitive devaluations, became widespread as countries prioritized domestic interests.

The collapse of the gold standard further destabilized international finance. In contrast to the cooperation seen before the war, countries pursued economic nationalism and isolationism.

Protectionism increased in the 1930s as a result of the dislocation caused by the Great Depression. In an attempt to shield domestic industries from foreign competition and address soaring unemployment, many countries imposed tariffs and trade barriers.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in the United States exemplified this trend, triggering a series of beggar-thy-neighbour policies. These protectionist policies exacerbated the downturn and contributed to a contraction in international trade that worsened the severity and duration of the Great Depression.

Mindful of the lessons of the 1930s, a more liberal economic order was established in the aftermath of World War II. The creation of the Bretton Woods Institutions – the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) – provided the principal mechanisms for managing and governing the global economy over the second half of the 20th century.

Building on the GATT, the formation of the World Trade Organization in 1995 provided the institutional framework for overseeing international trade and settling disputes. China became the 143rd member of the WTO in 2001 and almost all global trade became subject to a common set of rules.

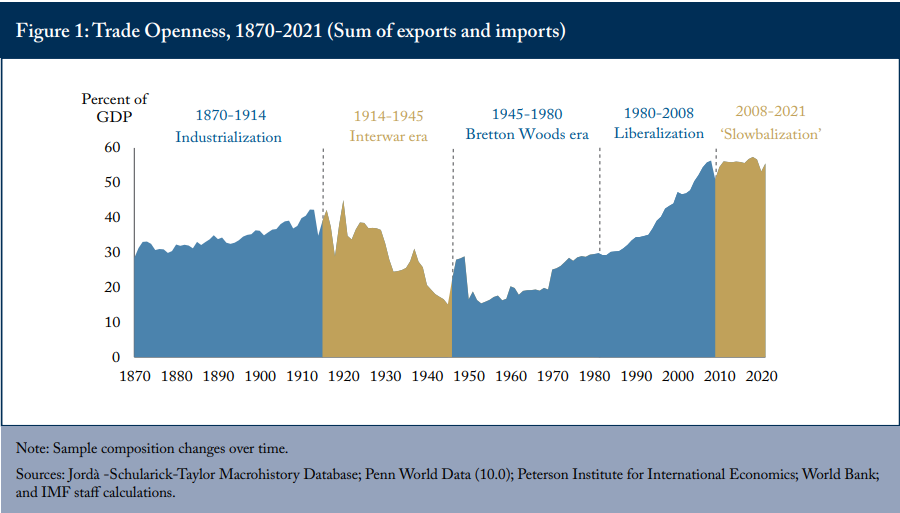

The rise and fall of international economic governance are reflected in the cycles of outcome-based measures of globalization. Looking at trade openness, i.e., the sum of exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, the IMF divides the process of global integration into five periods: (i) the

industrialization era, (ii) the interwar era, (iii) the Bretton Woods era, (iv) the liberalization era, and (v) “slowbalization” (Figure 1).

Many factors have contributed to the plateauing of trade openness in the last 10 to 15 years. The fallout from the Global Financial Crisis was severe and the recovery was tepid. Brexit, with its inward-looking perspective, has disengaged the UK from Europe.

Populist protectionism has led to “re-shoring” in an effort to address rising inequalities and labour’s falling share of national income. There has been far-reaching cyclical and structural fallout from COVID-19.

And while the AI revolution portends significant opportunities, uncertainties over labour displacement abound.

Geopolitics has also played a critical role. Security concerns have become more important, trumping economic issues in the eyes of many. This has led to multiple sanctions, along with export and investment controls, being imposed to protect national security interests.

The IMF has carried out several modelling exercises that estimate the consequences of fragmentation if further trade and technology barriers were to be imposed. The studies employ a variety of assumptions regarding trade restrictions and technology de-coupling. In summary, the cost of further fragmentation ranges from 1.5 to 6.9 percent of global GDP. As with all modelling exercises, a degree of caution is warranted. At the same time, these studies should not be viewed as upper-bound estimates because they disregard many other transmission channels of global economic integration. - De Jure and De Facto Globalization

In assessing the evolution of globalization, however, it would be misleading to focus too narrowly on outcome-based measures such as the trade-to-GDP ratio depicted in Figure 1.

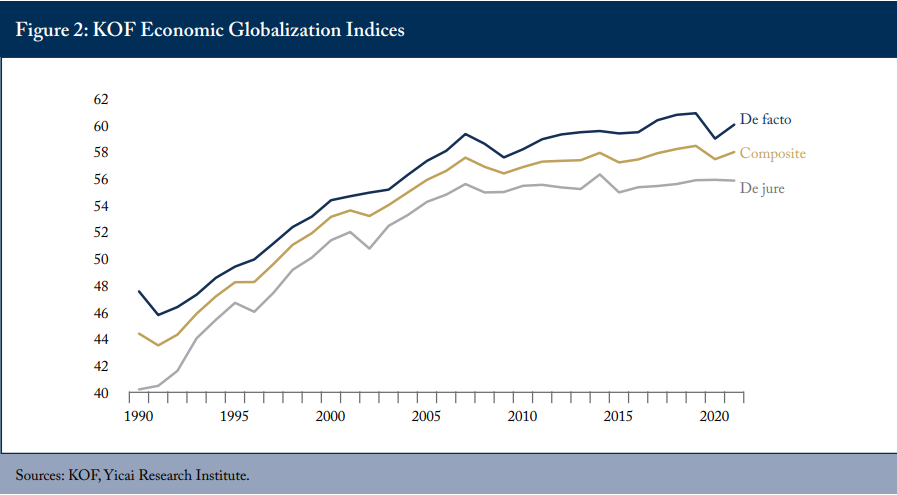

The data compiled by KOF, a Swiss research institute, provide a more nuanced view of global economic integration. KOF constructs globalization

indices that measure integration across economic, social, and political dimensions. Its globalization indices are among the most widely used in academic literature. KOF’s data set covers 203 countries over the period 1970 to 2021. Our focus here is on KOF’s economic indices.

In terms of economic globalization, KOF looks at the evolution of finance as well as trade. Moreover, one of the unique aspects of KOF’s work is that it examines globalization on both de facto and de jure bases.

KOF’s de facto globalization indices measure actual international flows and activities. In terms of trade, it includes cross-border goods and services flows and trading partner diversity. For financial globalization, its indices measure stocks of international assets and liabilities as well as cross-border payments and receipts.

KOF’s de jure globalization indices try to capture the policies and conditions that, in principle, foster these flows and activities. For trade globalization,

these include income from taxes on trade, non-tariff barriers, tariffs, and trade agreements. De jure financial globalization is designed to measure the institutional openness of a country to international financial flows and investments. Variables to measure capital account openness, investment restrictions and international agreements and treaties with investment provisions are included in these indices.

The trends in KOF’s de facto and de jure economic globalization indices are shown in Figure 2. Both globalization measures increased rapidly from 1990

until the Global Financial Crisis. Both measures subsequently plateaued. In 2020, as the global pandemic took hold, the de facto index plunged to its

lowest level since 2011. In 2021, it recovered half of the distance it lost the previous year. The de jure index has essentially been flat for the last decade.

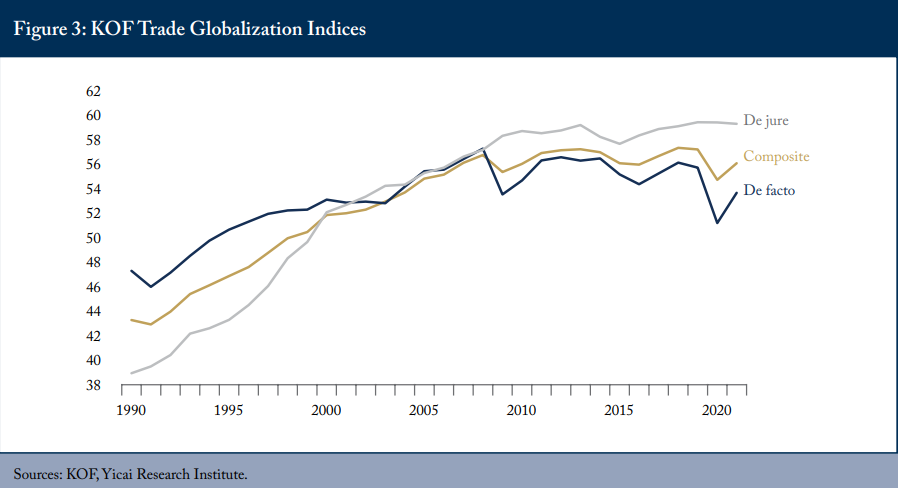

There has been a sharp divergence between KOF’s de facto and de jure trade globalization measures in the last five years (Figure 3). By 2020, de facto trade globalization had dropped to a 25-year low. Although it recovered somewhat in 2021, it remains well below the average of the last decade. In contrast, de jure trade globalization levelled off after the Global Financial

Crisis. It reached a modest new high in 2019 and has essentially remained there since then.

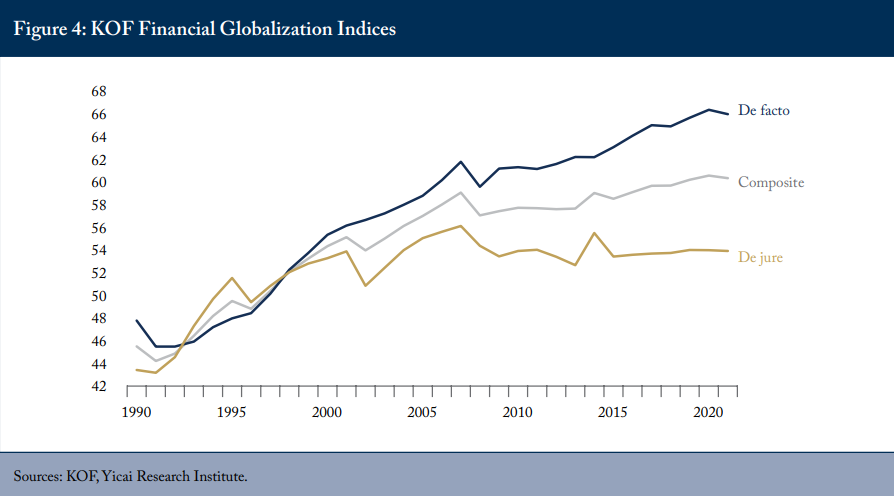

The trends in financial globalization are almost the reverse of those of trade globalization. De facto financial globalization continued to increase through

2020 and dipped slightly in 2021. De jure financial globalization has been essentially flat over the last two decades (Figure 4).

The KOF researchers provide convincing econometric evidence that economic globalization supports per capita GDP growth. Importantly,

their analysis shows that institutions matter. They demonstrate that the positive impact on growth from trade and financial globalization comes from

institutional liberalization rather than greater economic flows. Through a series of panel regressions, the researchers show that it is the de jure trade and financial globalization indices that are correlated with more rapid per capita GDP growth. In contrast, there is no significant relationship between growth and the de facto indices.

KOF’s conclusions are consistent with the work of Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi who examine the contributions of institutions, geography, and trade

in determining relative income levels around the world. They find that institutional quality “trumps everything else.” Once institutions are controlled for, conventional measures of geography have weak effects on incomes and the contribution of trade is generally not significant.

Thus, to recapture the economic benefits of free trade and open markets, countries need to recommit to finding ways to further de jure globalization; that is, putting in place the institutional building blocks in

support of enhanced trade and financial integration. - Geopolitical Realities

Institutional reform, however, requires trust and mutual respect among partners. Many would argue that such trust and respect is in limited supply

today, especially between the United States and China. The United States is willing to endure the costs of heightened protectionism to purportedly

strengthen the resilience of its economy and secure greater political security. This has resulted in multiple sanctions, particularly in areas of digital technologies.

In response, China, amongst other measures, has imposed export controls on critical minerals used in advanced technology in defence of its geopolitical goals.

Yet, as discussed by Fareed Zakaria in a Foreign Affairs article, The Self-Doubting Superpower, China has become the second largest economy in the world richer and more powerful within an integrated global economic system; a system that if overturned would result in severely negative consequences for China.

For the United States, its inherent strength has been its commitment to open markets and its vision of the world that has considered the interests of others. In many respects, it remains uniquely capable of playing the central role in sustaining the global economic system.

Following a recent trip to China, Treasury Secretary Yellen stated that “the relationship between the United States and China is one of the most consequential of our time,” and that it “is possible to achieve an economic

relationship that is mutually beneficial in the long-run – one that supports growth and innovation on both sides.”

This means that the United States would need to accommodate China’s legitimate efforts to sustain a rising standard of living for its citizens, while

deterring illegitimate ones. For China, it would mean a clear and abiding commitment to an open, rules-based global economic system.

It appears that there is currently no clear path forward for this change in mindset, given what many see as insurmountable geopolitics in both the United States and China. Yet, history shows that achieving and sustaining long-term economic growth is in every country’s best interest, and that such growth is best secured through ongoing global economic integration. - A Way Forward

Recent discussions at the IMF’s Annual Meeting in Marrakech about IMF quota reform, including quota increases and realignment in quota shares to

better reflect members’ relative positions in the global economy, are important signals of possible renewal.

Similarly, calls to revamp the World Bank’s mandate, operational model, and ability to finance global public goods, such as climate transition, reflect a growing consensus that the Bretton Woods Institutions must change in the face of today’s realities.

But institutional renewal alone is insufficient.

Broad-based accession to the CPTPP represents a unique opportunity to strengthen global governance overall, and to address common challenges in ways that benefit both countries as well as the global economy.

The CPTPP sets a high bar, requiring countries to:

- eliminate or substantially reduce tariffs and other

trade barriers; - make strong commitments to opening their markets;

- abide by strict rules on competition, government

procurement, state-owned enterprises, and

protection of foreign companies; and - operate within, as well as help promote, a

predictable, comprehensive framework in the critical

area of digital trade flows.

The United Kingdom formally agreed to join the

CPTPP in July 2023. Once its Parliament ratifies

the Agreement, the UK will join Australia, Brunei

Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico,

New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam in the

trading block.

Such a diverse membership clearly demonstrates

that countries do not have to be geographically close

to form an effective trading block.

A half-dozen other countries have also applied

to join the CPTPP, with China’s application having

been the earliest received.

Petri and Plummer estimate that joining the

CPTPP would yield large economic benefits for

China and the global economy. For the latter, the

boost to global GDP would be in the order of $600

billion annually. The United States in joining would

gain preferential access to rapidly growing Pacific Rim

markets. Much of the additional market access would

come from China’s opening of its service sector.

Industrial policy and state-owned enterprises,

however, will continue to play a much larger role

in China than they do in Western economies. The

key for China is to demonstrate that a socialist

market economy (i.e., one that has a mixed capitalist

market and government-controlled economy) can be

consistent with fair trade.

The process of China joining the CPTPP will

undoubtedly be time-consuming. It took 15 years of

negotiations before China joined the WTO in 2001.

This was five more years, on average, than it took

those countries that joined after 1995.

The challenge for Canada, and subsequent chairs,

is to ensure that China’s entry maintains the high

standards CPTPP members have met so far.

Broad based accession to the CPTPP, including

the United States and China, however, is best viewed

Page 8 Verbatim

Trusted Policy Intelligence

as a long-term goal. China would need to undertake

unprecedented reforms, involving complex political

challenges, including Taiwan’s potential accession. For

its part, the United States would need to step well

back from its current mercantilist mind set, which

risks worsening.

Canada as Chair in 2024

While efforts to renew existing global institutions to better reflect current economic realities are important, we see promoting broad accession to the CPTPP as the best means to turn today’s global economic fragmentation around.

At the heart of the global economic system is the open trading framework put in place at Bretton Woods in 1944. Many would see today’s fragmentation as becoming more acute, rather than getting better, due to geopolitical divisions.

But further fragmentation is no way to save the open, rules-based global trading system that has served so many countries so well for so long.

While restrictions reflecting legitimate security concerns are inevitable, an open, competitive trading system remains in the best interests of all countries.

As 2024 Chair of the CPTPP Commission, Canada has an opportunity to contribute to turning around the fragmentation of today’s global trading system and moving the global economy back along a path towards a

more open, rules-based trading system.

An important goal for Canada’s chairmanship would be to clarify the rules of accession. This would be a big step forward in sustaining expansion of CPTPP. While today’s geopolitical realities surrounding the applications of both China and Taiwan represent a particularly challenging area to advance, significant progress in other areas must be made. It should accelerate inclusion of Costa Rica, Uruguay, Ecuador, and Ukraine, all of whom have applied. And it should help move forward discussions with South Korea, Indonesia, Philippines, and Thailand, who have expressed interest in joining.

Over and above all that, however, at a more strategic level, Canada should also champion discussion and understanding of why building towards the long-run goal of broad accession to CPTPP is important. Open and inclusive institutions are at the core of providing the benefits of global economic integration to all countries.

Canada will also be Chair of the G7 Summit in 2025. This, along with the various ministerial and officials’ meetings leading up to the Summit, offers another critical avenue for Canada to take a leadership role in sustaining and promoting an open, rules-based global trading system.