No video game genre is as venerable, or as durable, as that of the simple adventure game. “Adventure” actually covers a number of styles, but there are a few distinguishing characteristics common to them all. They eschew action and combat in favor of exploration and puzzle-solving, and instead of developing their own in-game personas, players generally step into the shoes of an established, or at the very least fixed, character following a tightly-crafted narrative. Yet from the text-based odysseys of the 70’s and 80’s to the surprisingly sophisticated point-and-click journeys of today, the adventure in all its many variations has proven itself one tough old bird.

No video game genre is as venerable, or as durable, as that of the simple adventure game. “Adventure” actually covers a number of styles, but there are a few distinguishing characteristics common to them all. They eschew action and combat in favor of exploration and puzzle-solving, and instead of developing their own in-game personas, players generally step into the shoes of an established, or at the very least fixed, character following a tightly-crafted narrative. Yet from the text-based odysseys of the 70’s and 80’s to the surprisingly sophisticated point-and-click journeys of today, the adventure in all its many variations has proven itself one tough old bird.

The origins of the genre can be found in the 1976 game entitled Colossal Cave Adventure. Created by Will Crowther, it was based on his real-life caving experiences embellished with a smattering of fantasy elements that were later expanded upon by Stanford University graduate student Don Woods. Among its most ardent fans were Ken and Roberta Williams, who were so inspired by the game that they actually launched their own software house, Online Entertainment, later famous as Sierra Online, one of the foremost game publishers of the 80s and 90s and an early pioneer of the graphical adventure.

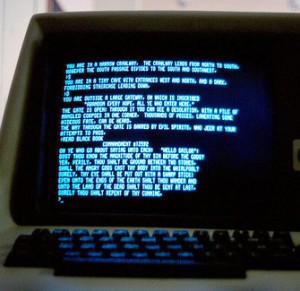

While Sierra was innovating with graphics, another company known as Infocom was pushing boundaries of a different sort. Infocom games like Zork, Planetfall and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy were all about the text parser, yet they were also engaging, complex and, for awhile, commercially successful. But unlike Sierra, Infocom was late catching the graphical wave; its sales declined throughout the second half of the 1980s until Activision, which acquired Infocom in 1986, shut it down for good in 1989.

The next big thing in adventures was LucasArts. These days the company is best known for churning out half-baked Star Wars titles but there was a time when the name evoked images of rough-hewn bikers, invading alien tentacles, Freelance Police and some of the most unlikely pirates you’re ever likely to meet. In 1993, Cyan changed everything with Myst, an incredibly popular and influential release that discarded many of the conventional rules of the genre and made exploration and the discovery of everything, including the basic rules of play, an integral part of the experience.

Today, adventures no longer set the pace for the industry they way they once did (perhaps things are changing- L.A. Noir aims to refresh the adventure genre in high style- content producer) but they have enjoyed a resurgence in recent years in the hands of small, independent developers who continue to innovate and refine. One of the most remarkable examples of the current state of the adventure art is Gemini Rue, which actually roots itself in the past with blocky, VGA-style graphics that manage to look both dated and yet surprisingly beautiful. But underneath those retro visuals lies a thoroughly modern game, with a haunting soundtrack, top-flight voice acting and a story that will keep you guessing until the very end – and leave you wanting more.

The humble adventure has long since been surpassed in popularity by the shooter, the RPG and other genres, but the emergence of gaming as a mainstream creative medium, coupled with the near-limitless potential of widely accessible digital distribution, could very well herald a renaissance. This in turn opens the style to a wider audience than ever, and while not every gamer will like every adventure – personally, I can’t stand King’s Quest games – I can just about guarantee that ever gamer will find one or two that suit their tastes. Try one sometime. You might be surprised. For the Silo, Andy Chalk.

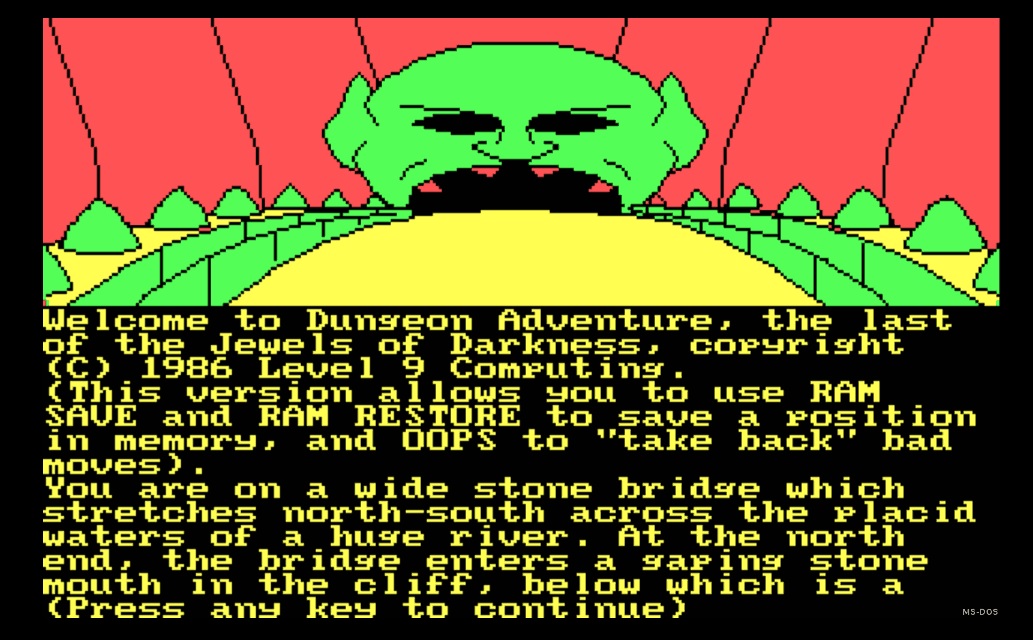

Featured image- The Jewels of Darkness Trilogy (all 3 Colossal Cave Adventure games/sequels) MS-DOS 1986