[This article was first published by The Silo on April 22, 2014] On June 10, 2009, the Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair, Marie Wilson and Chief Wilton Littlechild were appointed as Commissioners to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), a component of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is unique from other commissions around the world in that its scope is primarily focused on the experiences of children and its research spans more than 150 years (one of the longest durations ever examined). It is also the first court-ordered truth commission to be established and most notable, the survivors themselves set aside 60 million dollars of the compensation they were awarded to help establish the TRC.

Over the course of its 5 year mandate, one of the main tasks of the Commission is to create an accurate and public historical record of the past regarding the policies and operations of the former residential schools, what happened to the children who attended them, and what former employees recall from their experiences.

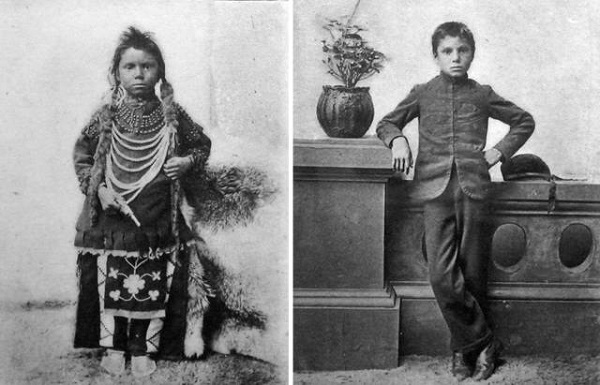

It is difficult for Canadians to accept that the policy behind the government funded, church run schools attempted to “kill the Indian in the child”. The violent underpinnings of the policy challenge the way we think about Canada, and call into question our national character and values. We have been taught to believe that we are a peaceful nation, glorious and free.

The residential school legacy shines a light in our darkest corners, where we feel most vulnerable.

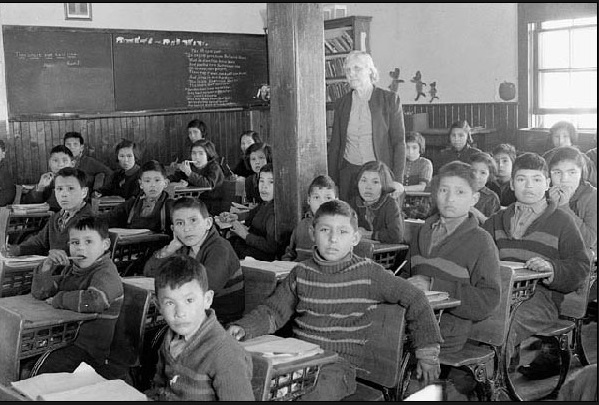

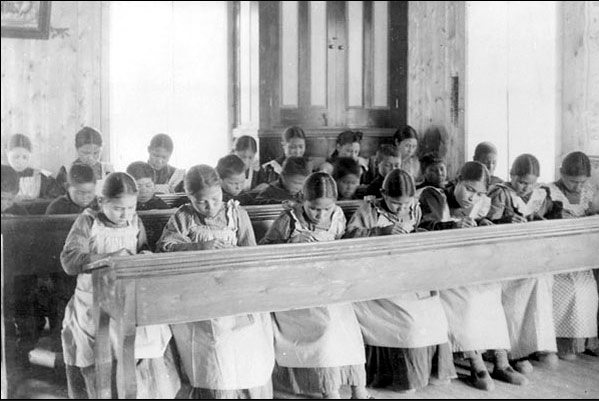

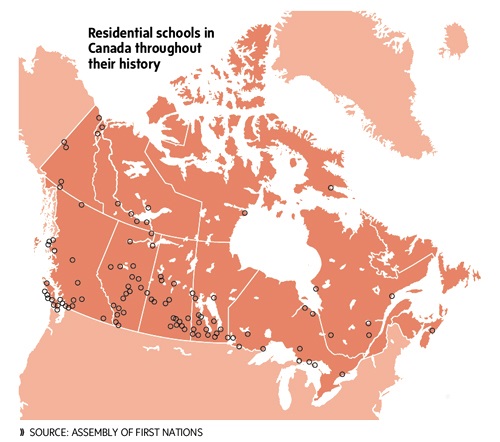

Over 130 Residential Schools were located across Canada, with the last one closing in 1996. More than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children as young as five years old were forcibly removed from their families and placed in institutions that shamed their languages, customs, families, communities, traditions, cultures and history. In essence, they were not allowed be themselves and denied the love and belonging owed to all children.

While some former students had positive experiences at residential schools, many suffered emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and others died while attending these schools. Other lessons in trauma included assimilating children to gender roles, non-skilled labour and religion to prepare them for future integration. For the parents left behind, the worst lessons in shame, grief, loss and disconnection. Whole societies were undone.

In addition to creating the public historical record of the past, the survivors also tasked the Commission to reveal to Canadians the full and complete story.

What were they thinking? Why should it matter to ordinary Canadians?

Here’s why: When we tell our stories we change the world. When we don’t tell our stories we miss the opportunity to experience empathy and to cultivate authenticity, joy and belonging. (Brené Brown, 44) Through story-telling, the survivors are compelling Canadians to listen and respond with deep compassion and to re-set relationships in a big way in this country. This is our greatest opportunity to recognize shared history and our shared humanity. These stories are a gift and will help us to shape our shared future.

Through statement gathering at national or regional events and at TRC Community Hearings, former students, their descendants and anyone who has been affected by the Residential Schools legacy, had an opportunity to share their individual experiences in a safe and culturally supportive environment. The TRC concluded its last community hearing in March 2014 and has collected more than 6, 200 statements.

Almost all of them were video-and-audio-recorded and range from a few minutes to a few hours. The statements will be stored at the National Research Centre on Indian Residential Schools at the University of Manitoba. Students, researchers and members of the public will be able to access the statements to learn about residential schools and the legacy they leave behind.

As the TRC begins to reveal to Canadians the full and complete story of residential schools and inspire a process of reconciliation across this country, ordinary Canadians seem ill-equipped to make the journey from shame to empathy. “We know the voices singing, screaming, wanting to be heard- but we don’t hear them because fear and blame muffle the sounds” (Brené Brown, 42) We need to prepare ourselves to go to the dark corners of our history, so we can stand in the light together as equals.

In my next article, I will share with you more about empathy, how to practice empathy and why its essential to building meaningful and trustworthy relationships.) For the Silo, Leslie Cochran.

(Brené Brown, 42 and Brené Brown, 44) are taken from her first book “I thought it was just me.”

Ontario Apologizes for Residential Schools

Government Releases Action Plan for Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples

May 30, 2016 Premier Kathleen Wynne apologized today on behalf of the Government of Ontario for the brutalities committed for generations at residential schools and the continued harm this abuse has caused to Indigenous cultures, communities, families and individuals.

The Premier made her Statement of Ontario’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples in the Legislative Assembly, with residential school survivors and First Nation, Métis and Inuit leaders in attendance. She apologized for the policies and practices supported by past Ontario governments, and the harm they caused; for the province’s silence in the face of abuse and death at residential schools; and for residential schools being only one example of systemic intergenerational abuses and injustices inflicted upon Indigenous communities throughout Canada.

In recognition of this historic event and Ontario’s nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples, the Legislature voted unanimously to open the floor to speeches from Opposition party leaders, Indigenous leaders — and from Andrew Wesley, a residential school survivor who attended St. Anne’s Indian Residential School in Fort Albany in his youth.

The Premier’s apology is part of the government’s response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Final Report, released one year ago. Ontario is taking action to acknowledge one of the most shameful chapters in Canadian history and teach a new generation the truth about our shared history. The province released an action plan today — developed working closely with Indigenous partners — that will help Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples move forward in a spirit of reconciliation.

The Journey Together: Ontario’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples plans to invest more than $250 million over three years in new initiatives in five areas:

Understanding the legacy of residential schools: The province will ensure that Ontarians develop a shared understanding of our histories and address the overt and systemic racism that Indigenous people continue to face

Closing gaps and removing barriers: Ontario will address the social and economic challenges that face Indigenous communities after centuries of colonization and discrimination

Creating a culturally relevant and responsive justice system: The province will improve the justice system for Indigenous people by closing service gaps and ensuring the development and availability of community-led restorative justice programs

Supporting Indigenous culture: Ontario will celebrate and promote Indigenous languages and cultures that were affected after generations of Indigenous children were sent to residential schools

Reconciling relationships with Indigenous Peoples: The province will support the rebuilding of relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people through trust, mutual respect and shared benefits. These commitments are just some of many steps on Ontario’s journey of healing and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. They reflect the government’s commitment to work with Indigenous partners to build a better future for everyone in the province.

“No apology can change the past, nor can the act of apology alone change the future. We must

change the future — together — day by day and generation by generation. In making this

apology and through this action plan, I hope to demonstrate our government’s commitment to

changing the future by building relationships based on trust, respect and Indigenous Peoples’

inherent right to self-government.”

–– Kathleen Wynne, Premier of Ontario

“Canada’s residential school system is a dark chapter in our history. Children as young as five

years old were removed from their homes, and that legacy of attempted cultural genocide is still

felt to this day. By working with Indigenous partners to close gaps in health, education and

employment, Ontario is helping to repair the damage and provide opportunities to Indigenous

people that were taken away from previous generations.”

–– David Zimmer, Minister of Aboriginal Affairs

QUICK FACTS

The first residential school in Ontario opened in 1832. The last one closed 25 years ago, in

1991.

There were 18 residential schools in Ontario, attended by children aged 5 to 14.

Children in residential schools were up to five times more likely to die than their counterparts

in the rest of Canada.

Indigenous people make up 2.4 per cent of Ontario’s population, but about 25 per cent of

children in foster and customary care in Ontario at any given time are Indigenous.

As part of The Journey Together, the Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs will be renamed the

Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation.

The government has introduced mandatory Indigenous cultural competency training for all

employees of the Ontario Public Service.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s final report, released last December,

included 94 Calls to Action. These urged all levels of government to work together to repair

the harm caused by residential schools and move forward with reconciliation.

LEARN MORE

The Journey Together: Ontario’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples

Be part of Ontario’s journey and submit your hope for reconciliation on the ReconciliationTree

Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada